Female Sexual Dysfunction

WHEC Practice Bulletin and Clinical Management Guidelines for healthcare providers. Educational grant provided by Women's Health and Education Center (WHEC).

Sexual intimacy is an integral part of life and is closely linked to emotional and physical well-being. Sexual dysfunction encompasses a broad spectrum of issues in the psychological, physical, interpersonal, and physiological realms. Change in sexual dysfunction creates substantial distress for some women, but ever since an oft-quoted 1999 study concluded that a whopping 43% of US women between ages 18 and 59 years have sexual dysfunction (1), the variations of the norm are morphing into diseases. In that study, 27-32% of women in various age categories reported a lack of interest of sex, compared with 13-17% of men. Such gender differences are attention-grabbing and lead to all sorts of physiologic, sociologic, and psychological questions. In a global survey of the importance of sexuality and intimacy in 27,000 men and women aged 40 to 80 years, 83% of men and 63% of women rated sex as extremely important, very important, or moderately important in their lives (2). Despite the importance of a healthy sex life to most people, research suggests that sexual dysfunction is common. Female sexual dysfunction is a term used to describe various sexual problems, such as low desire or interest, diminished arousal, orgasmic difficulties, and dyspareunia. Most epidemiologic definitions of female sexual dysfunction refer to sexual problems without requiring sexually related personal distress to be present, whereas current diagnostic guidelines from the American Psychiatric Association and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) require personal distress as part of the diagnostic criteria for "dysfunction". Counseling individuals and couples regarding sexual difficulties is generally a daunting process. Yet people do seek treatment, with the hope of improving their personal lives. Notably, men and women are more willing to talk about their sexual behavior when the "interview is conducted in a respectful, confidential and professional manner".

The purpose to this document is to discuss the etiology and diagnosis of female sexual dysfunction and the discussion below offers basic therapeutic approaches to the management of sexual complaints. While pharmacologic options for treating male sexual dysfunction continue to proliferate, the development of such drugs for women has lagged far behind. Now, however, a number of agents are emerging that may help to fill this gap. A discussion of the detailed evaluation and management of dyspareunia and vaginismus is beyond the scope of this article; however, diagnosis of an underlying etiology for the pain should be sought. Both disorders can benefit from education, pelvic floor physical therapy (including biofeedback and massage), and psychological counseling.

Defining Dysfunction

The definition of sexual health as defined by World Health Organization (WHO): it is a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity. Sexual health requires a positive, respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships and the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. For sexual health to be attained and maintained, the sexual rights of all persons must be respected, protected and fulfilled (3). The fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) divides female sexual dysfunction into four categories:

- Hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) -- a persistent or recurrent deficiency or absence of sexual fantasies and desire for sexual activity. Sexual aversion disorder, a subset of HSDD, is defined as -- the persistent or recurrent phobic aversion to and avoidance of sexual contact with a sexual partner, which causes personal distress (4).

- Female sexual arousal disorder -- a persistent or recurrent inability to achieve or maintain adequate vaginal lubrication or vulvar swelling (i.e., sexual excitement). In 2003 the American Urological Association Foundation; subdivided arousal disorder into:

- Combined arousal disorder -- absent feelings of sexual arousal from any type of stimulation, as well as absent or impaired genital sexual arousal (vulvar swelling and vaginal lubrication).

- Subjective arousal disorder -- absent feelings of sexual excitement and pleasure from any type of stimulation in the presence of genital sexual arousal (vulvar swelling and vaginal lubrication).

- Genital arousal disorder -- subjective sexual excitement from non-genital sexual stimuli with reduced sensation from genital touching and an absence of genital sexual arousal from any type of sexual stimulation.

- Female orgasmic disorder -- persistent or recurrent delay in or absence of orgasm following a normal sexual excitement phase.

- Sexual pain disorder -- this disorder is subdivided into three categories:

- Dyspareunia -- persistent and recurrent genital pain associated with sexual intercourse.

- Vaginismus -- persistent or recurrent involuntary spasm of the outer third of the vaginal musculature, leading to pelvic pain and personal distress.

- Non-coital sexual pain -- persistent and recurrent pelvic pain induced by non-coital sexual stimulation (4).

It is imperative that we begin to understand the nuances of our patients' sexual problems if we are to offer effective suggestions for treatment and management. Objectively determined genital arousal disorder very likely derives from neurovascular causes and is likely to respond to phosphodiesterase type-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors, but subjective arousal disorder with normal vulvar and vaginal examination the lubrication is not likely to respond to these agents. The complexity of sexual arousal disorders in women complicates research into patho-physiology and potential pharmacologic treatment of these conditions. Conflicting evidence for any benefit of the PDE5 inhibitors, such as sildenafil, in the treatment of sexual dysfunction in women likely arises from a lack of precision in defining the conditions in patients for whom these interventions are appropriate.

Background

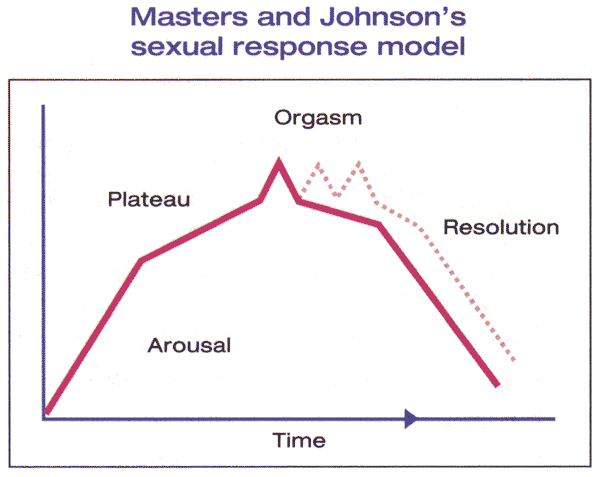

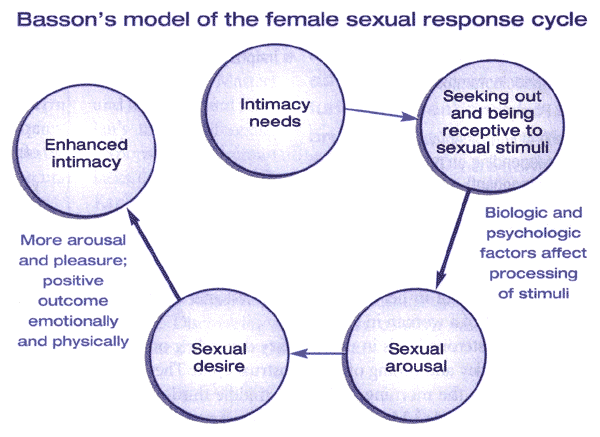

Based on the landmark research in the 1960s, Masters and Johnson developed a linear, 4-stage model of sexual response, which included the phases of excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution. Kaplan proposed an alternate model in 1979 and introduced the concept of desire as the first stage of the normal sexual response cycle. In this model, desire leads to arousal, then plateau, followed by orgasm and resolution. This model has been widely accepted, and most definitions view sexual dysfunction as an interruption of 1 or more phases of this response cycle. This model was intended to reflect sexual response for males and females; however, researchers have recognized that some women do not experience all 5 phases of the cycle and/or may not do so in the sequential progression described. As such, this model has been criticized since it may not reflect a woman's actual experience (5). Basson proposed an alternative model to the traditional linear model to account for the complexity of female sexuality and its core need for closeness and emotional intimacy. This cyclic model is based on intimacy and incorporates integral sexual stimuli, which can be influenced by biological and psychological factors. Spontaneous desire, such as sexual thoughts and conscious wanting and fantasizing, can augment the cycle as well. This model reflects the dependency on the interaction of mind and body of sexual functioning in women (6). Spontaneous sexual desire drive may or may not be present, especially as a woman ages (7). For many women, the goal of sexual activity is intimacy, and they may seek out sexual encounters for this purpose. In response to sexual stimuli, arousal may ensure and desire may then follow. The peak emotional experience and emotional and physical satisfaction may or may not coincide with physical satisfaction or with physiological release that occurs during orgasm. Indeed, there may be an infinite variety of sexual responses for women.

n

Figure 1. The Masters and Johnson model describes a woman's arousal cycle as consisting of four steps: arousal, plateau, orgasm, and resolution. The model includes the ability of women who have reached the orgasm stage to experience multiple orgasms (dotted line).

Figure 2. The Basson model of female sexual response combines the elements of Masters and Johnson's model (arousal, plateau, orgasm, resolution) and Kaplan's model (desire, arousal, and orgasm), while also incorporating the desire for intimacy and the importance of emotional needs.

Predisposing Factors

The vast majority of sexual problems are caused by a variety of factors, often a combination of biological, psychological, and relationship issues. Some medical and surgical conditions can contribute to sexual difficulties as can gynecologic causes. Conditions that affect energy and overall well-being may indirectly affect sexual desire and response as well. Also, conditions that alter the hormonal milieu can impede the sexual response. Neoplastic disease and its treatment, including chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery, can present mortality concerns, alter or remove physical and psychological symbols of femininity, and affect self-esteem, all of which may result in feelings of decreased sexuality. Treatment of non-neoplastic diseases or their treatment can change body image and self-esteem and can affect sexuality. Essentially, any medication that alter blood flow, affects the central nervous system, causes dryness of the skin and mucous membranes, or adversely affects the levels of bioavailability androgens can potentially interfere with normal sexual function.

Cardiovascular causes: hypertension; coronary artery disease; angina; previous myocardial infarction.

Renal causes: chronic renal disease; renal failure; dialysis.

Endocrine causes: diabetes; thyroid disorders; hyperprolactinemia; adrenal disorders; pituitary disorders.

Musculoskeletal causes: arthritis; Sjögren's syndrome; autoimmune diseases.

Neurologic causes: multiple sclerosis; spinal cord damage; Parkinson's disease; peripheral neuropathies; cerebrovascular events; dementia.

Urinary causes: incontinence.

Gynecologic causes: infections (Bartholin's or Skene's gland infections, cystitis, focal vulvitis); intact hymen or thick hymeneal tags; vulvar dystrophy; dermatitis; vaginal atrophy; scarring (from episiotomy, vaginal surgery, or radiation); vulvar vestibulitis; vaginismus; pelvic infection (pelvic inflammatory disease, endometritis); pelvic masses (including fibroids); endometriosis; interstitial cystitis; cystocele, rectocele, uterine prolapse; oophorectomy; gynecologic malignancies and treatment.

Other causes: breast cancer/mastectomy; colostomy; urostomy; skin disorders; alcohol and substance abuse; tobacco abuse.

Effect of medications on sexual function:

| Medication | Disorder |

|---|---|

Antihypertensives

|

Desire, arousal Arousal Desire, arousal Arousal Desire, arousal |

Psychoactive medications

|

Desire, arousal, orgasmic Desire, arousal, orgasmic Desire, arousal, orgasmic Desire, orgasmic Desire, arousal Arousal |

Hormonal agents

|

Desire, arousal Desire Desire Vaginal dryness, dyspareunia Desire |

| Anticholinergics | Arousal |

| Antihistamines (H1 and H2 blockers) |

Desire, arousal |

| Amphetamines and related drugs | Arousal, orgasmic |

| Narcotics | Desire, arousal, orgasmic |

| Sedatives (including alcohol) | Desire, arousal, orgasmic |

Screening for Sexual Disorders

Although sexual dysfunction is common, it is a topic that many people -- patient and physician alike -- are hesitant to discuss. In data obtained from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP), only 38% of men and 22% of women aged 57 to 85 reported having discussed sex with a physician since age of 50, despite the high prevalence (>50%) of sexual problem (8). Physician-initiated questioning about sexuality has been shown to significantly increase patient reporting to sexual dysfunction (8) and should, therefore be incorporated into regular practice. All patients should be screened for sexual dysfunction, and perhaps the most natural time to do so is at the annual or periodic health visit. In terms of screening, a brief sexual status history can be covered with four basic questions:

- Are you sexually active?

- Is your sex life satisfying to you?

- Is your sexual activity satisfying for your partner?

- Do you have any concerns about your sex life or functioning?

A questionnaire can also be incorporated into a patient intake form and used as a pre-consultation screening tool is desired. The evaluation of a patient complaining of sexual dysfunction should include a detailed medical and sexual history, a complete physical examination, and laboratory tests, if indicated. Areas that may be assessed about any pain or discomfort, any previous treatment, first sexual experience, early teaching regarding sexuality, sexually transmitted infections, pregnancies and history of sexual problems. Psychological, social and relationship histories are also needed. The patient should be evaluated for anxiety and depression because of their potential effect on intimacy and desire. The partner can often be an important source of information. Therefore, it may be beneficial to have the partner present at some point during the office visit and during the education process.

The Oxford Grading System can be used to quantify the degree of pelvic floor muscle dysfunction (9). After a thorough history and physical examination, a validated and reliable sexual function questionnaire, such as the Sexual Function Questionnaire or Female Sexual Function Index, should be administered to further quantify and qualify the diagnosis. These questionnaires, which examine six different domains (arousal, orgasm, desire, lubrication, pain and overall satisfaction), have been shown to be reliable evaluative tools for screening. The results from the different domains will help to identify the subtype of female sexual dysfunction affecting the patient. The prevalence of distressing sexual problems usually peaks in middle-aged women and is considerably lower than the prevalence of sexual problems (10). This underlines the importance of assessing the prevalence of sexually related personal distress in accurately estimating the prevalence of sexual problems that may require clinical intervention.

Approach to Management

Female sexual dysfunction is multifactorial, often with several different etiologies contributing to the problem. Nonetheless, careful evaluation and use of available therapies can improve sexual function for many women. Assess patient goals prior to starting treatment and use her goals to evaluate progress. This also gives the clinician the opportunity to set realistic patient expectations. While some may desire modest improvements in their sexual life, others may expect that treatment will allow them to achieve an ideal based upon past experience or cultural images of sexuality. Assess for and treat associated conditions before and during sexual dysfunction therapy. Sexual dysfunction can be complex and their treatment can be time intensive and require special expertise. With the patient's consent, communication and management decisions should be shared between the patient's clinician and other health care providers who treat the patient (e.g., cardiologist, psychiatrist). Also referral to psychotherapists, sex therapists, or pelvic physical therapists is often needed to address specific aspects of treatment. In addition, for women with partners, the partner must be involved in the treatment. This may include treatment of the partner's sexual dysfunction, if present, and/or involvement of the partner in working with continuing relationship issues (11).

Challenges to evaluating treatments: One measure that can be quantified and compared among studies is an event log, which is the frequency of sexually satisfying events. However, an event log does not typically assess qualitative changes in sexual function, such as sexual interest or level of distress. Most studies of sexual dysfunction treatment use validated questionnaire scores as an outcome measure. There are multiple questionnaires, which use different questions and scales. This makes it difficult to compare data between studies and treatments. Female sexual dysfunction typically affects more than one aspect of sexuality (e.g., desire, arousal) and most therapies also impact several aspects. Thus it is not generally possible to identify an isolated sexual issue and select a therapy that specifically targets that concern. The principal predictors of sexual satisfaction are physical and mental health, and the quality of the relationship with the partner, so the focus of therapy should be on interventions that optimize health, well-being and the partner relationship.

Non-Pharmacologic Therapies

As all currently available pharmacologic therapies for female sexual dysfunction are of limited efficacy and associated with side effects and potential risks, non-pharmacologic options should comprise the initial treatment for most women.

Counseling -- Psychological and relationship issues often underlie, exacerbate, or are amplified by sexual dysfunction in one or both partners. As an example, a major cause of decreased sexual desire and response is a relationship with limited communication or underlying conflict.

Lifestyle changes -- Fatigue, stress and lack of privacy contribute significantly to low libido and sexual problems for women. Often reducing stress with support group, yoga or other relaxation techniques or exercise, or assistance with childcare responsibilities and housework results in improved sexual interest and satisfaction. Encouraging couples to establish a regular "date-night" and to spend an occasional night or two away from family responsibilities can lead to significant improvements in sexual interest. Research on sexual function consistently demonstrates increased libido and pleasure in new relationships. Although women and men should not be advised to improve their sex lives simply by seeking out new partners, they should be encouraged to bring novelty to their current relationships. Reading books about sexuality, visiting a store with items designed to increase sexual pleasure and expanding the typical sexual repertoire effectively increase libido and response.

Sex and couple therapy -- Women with sexual dysfunction will often benefit from referral to a sex and/or couple therapist. Sex therapists often are highly trained counselors, with special expertise in human sexuality. They may be physicians, psychologists or social workers with additional training and experience. Sex therapists educate women and men about the normal sexual response cycle and effectively deal with cultural or religious concerns regarding sexuality. Examples of sex therapy exercise include instruction in the appropriate use of vaginal dilators, which is highly effective in treating most cases of vaginismus and dyspareunia. Communicating sexual likes and dislikes, in a non-judgmental manner; can reinvent novelty and improve satisfaction. It is often necessary to help a couple reestablish intimacy. One such approach includes the use of behavior therapy in the form of sensation-focus exercises or sensual massage, where one partner provides the massage and the other partner provides feedback. There is initially no involvement of sexual areas. The idea is to enhance comfort and communication between partners, eliminate performance expectations, augment awareness of bodily sensations, remove the genital focus, and broaden the sexual repertoire (12). Given the efficacy and high degree of safety of sex therapy, consultation with a sex therapist generally should be considered a prerequisite to a trial of pharmacologic therapy for most women with sexual dysfunction.

Pelvic physical therapy -- Physical therapists with subspecialty training in pelvic anatomy and function are very helpful for patients with dyspareunia, vaginismus, and pelvic pain (13).

Psychodynamic therapy -- Although relationship counselors and sex therapists are very helpful for psychologically healthy individuals, women with psychiatric disease will benefit from appropriate referral. Psychiatric disease, especially depression and anxiety, is associated with an increased likelihood of sexual dysfunction (14). Treatment of the underlying psychiatric problem, with appropriate pharmacology and/or psychodynamic therapy can lead to an improved sexual life.

Improving body image -- A woman's view of her own body affects her sexual interest and satisfaction. Overweight women with sexual dysfunction should be assisted with weight loss. In addition, many women experience no improvements in their sex lives when they initiate a regular exercise program.

Lubricants -- Lubricants during intercourse and non-hormonal vaginal moisturizers can be useful for both pre- and postmenopausal women with vaginal dryness and dyspareunia (15).

Devices -- A clitoral suction vacuum device, EROS CTDT, is Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for female sexual dysfunction. Its design is similar to vacuum devices used for male erectile dysfunction. It may improve local arousal and response by improving clitoral blood flow (16). The device is expensive and likely no more effective than less costly devices available without a prescription, such as vibrators.

Herbal Supplements

Many women are interested in trying over-the-counter herbal supplements, which are advertised widely and claim to increase sexual desire and pleasure. Women should be informed that the safety and efficacy of these products are unproven, there is minimal regulatory oversight, and they are often costly. Nonetheless, given a 30% predicted placebo response and few reported side effects, women may elect a trial of these alternatives. One such product is a proprietary blend of herbal supplements (Avlimil T). Many of the components of Avlimil T are estrogenic, and animal study data suggest that the product may stimulate growth of estrogen-dependent breast tumors (17).

Hormone Therapy

The therapeutic choices for male sexual problems have advanced rapidly in recent years, and include both hormonal and non-hormonal options for improving or correcting erectile difficulties. By contrast, female sexual pharmacology is extremely limited. Although hormones have been the mainstay for treatment for female sexual complaints, they are not FDA-approved for this indication.

Androgens

Levels of endogenous androgens do not predict sexual function; however, androgen therapy that increases serum concentrations to the upper limit of normal has consistently been shown to improve female sexual function in selected populations of postmenopausal women (18). The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) further states that such therapy can be considered in postmenopausal women if they present with decreased sexual desire associated with personal distress and no other identifiable cause for their sexual complaint. Finally, NAMS states that laboratory testing of testosterone level should not be used to diagnose testosterone insufficiency. Laboratory assays are not accurate for detecting testosterone concentrations at a low values typically found in postmenopausal women (18). Discussion of androgen therapy with a patient must include a full explanation of the potential benefits and risks. Women should understand that data on safety and efficacy are limited, including data on long-term use, or use without concomitant estrogen therapy.

Available androgen preparations -- The two preparations of testosterone that are convenient and are most likely to achieve therapeutic levels are: 1) topical compounded 1% testosterone cream (0.5 grams daily) applied to the skin of the arms, legs or abdomen or 2) Intrinsa™ 300 mcg testosterone patch applied twice weekly (available in Europe).

Various products in use include:

- Oral -- methyltestosterone, micronized testosterone (must be compounded; prescription only), dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA).

- Transdermal -- testosterone patches and gels formulated for hypogonadal men; Intrinsa 300 mcg testosterone patch for postmenopausal women (available in Europe), testosterone ointment or cream (compounded topical 1% or 2% by prescription).

- Injectable or implants -- intramuscular testosterone injections, testosterone implants.

Use of oral formulations is limited by the potential for adverse changes in lipids and liver function tests following first-pass hepatic metabolism (19). Methyltestosterone in combination with estrogen (Estratest) was taken of the United States market in 2009. DHEA is available without a prescription; doses of 25 to 50 mg/day raise circulating levels into the physiologic range (19). As this product is subject to minimal regulatory oversight, hormone content is highly variable. Women should not be given transdermal products formulated for men, such as skin patches (e.g. Androderm™) and gel (e.g. Androgel™). If they are used, careful dose adjustment is required, as excessive dosing will result from standard doses prescribed for men. Cutting patches is not advised, as no data are available on product stability or resulting testosterone levels. Gels would need to be applied in approximately 1/10th the male prescribed dose, as testosterone levels in women are approximately 10% those of men. As majority of controlled data on the efficacy and safety of testosterone therapy for postmenopausal with HSDD was obtained using a testosterone transdermal patch (Intrinsa™ 300 mcg), these patches may be the preferred product for women electing testosterone therapy.

Effectiveness -- Testosterone is primarily used to treat issues with sexual desire or responsiveness, although all aspects of sexual function generally improve, including arousal and orgasmic response. The largest series of controlled clinical trials (20) have utilized a transdermal testosterone patch delivering 300 mcg/day testosterone in postmenopausal women with HSDD. Regarding dosing, in general, trials indicate that a dose of 300 mcg/day for six months is safe and effective in women who are receiving concomitant estrogen therapy. There are no differences in treatment efficacy between women with natural versus surgical menopause. Regarding safety, breast cancer was diagnosed in four women who received testosterone, as compared with none who receive placebo. Although two of the cases likely were present prior to testosterone administration, the authors concluded that long-term effects of testosterone, including effects on the breast, remain uncertain. When considering androgen therapy in women of reproductive age, inadvertent exposure of a developing fetus must be considered a significant potential risk.

Adverse effects and contraindications -- Androgen therapy in women can potentially result in androgenic, metabolic, or endocrine adverse effects (19)(20). Androgens should be used with caution in women at risk for, or who currently have cardiovascular disease, hepatic disease, endometrial hyperplasia or cancer, or breast cancer. Major issues regarding side effects include -- cosmetic androgenic effects, such as hirsutism and acne; irreversible virilizing changes (e.g. voice deepening, clitoromegaly). Most androgens are aromatized to estrogens, thus risks of estrogen therapy are also possible with androgen treatment.

Monitoring androgen therapy -- Women on androgen therapy should be monitored for potential adverse effects. Given potential effects on lipids and liver function, normal values should be confirmed prior to initiating androgen therapy, reassessed approximately six months after starting treatment, and then annually thereafter. Abnormal uterine bleeding or breast symptoms (e.g. lump, nipple discharge) require appropriate evaluation. Annual mammograms should be performed in women receiving androgen therapy. Measuring a free testosterone level or free androgen index (total testosterone/sex hormone binding globulin) in women using topical testosterone therapies may be used as a safety measure, with the goal of keeping the value the value within the normal range reproductive aged women provided by the testing laboratory. Testosterone levels should not be used in determining the etiology of a sexual problem or in assessing efficacy of treatment, as several large, well-designed studies confirm the absence of a significant association between androgen levels and sexual function (21).

Estrogens

Although evidence does not support a role for systemic postmenopausal hormone therapy in the treatment of sexual problems, if a woman with a previously satisfying sex life presents with sexual problems concurrent with the onset of hot flashes, night sweats, sleep disruption and resulting fatigue, treatment of menopausal symptoms with systemic postmenopausal hormone therapy may lead to improvement in the sexual problem. The majority of postmenopausal women will develop urogenital atrophy in the absence of estrogen therapy. Urogenital atrophy is perhaps the most common cause of arousal disorders in postmenopausal women. Treatment of atrophy with a local vaginal estrogen cream, ring or tablet can be effective. Systemic estrogen therapy can be considered if there are no contraindications to its use and may be superior to local therapy alone when there is coexisting HSDD. The transdermal route of administration may be preferred to oral estrogen supplementation to avoid an increase in sex hormone-binding globulin levels and a subsequent decrease in bioavailable testosterone (22).

Bupropion

This antidepressant, a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and dopamine agonist, has been recognized for its lack of sexual side effects -- in contrast to other psychoactive drugs such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Bupropion is a weak blocker of serotonin and norepinephrine uptake, and has also been used for smoking cessation. A typical trial starts at a dose of 75 mg/day, increasing gradually as needed. Side effects include insomnia, nervousness, and mild to moderate elevations in blood pressure, as well as risk of lowering the seizure threshold. A landmark study assessed an escalating dose of bupropion with idiopathic acquired or global HSDD in a randomized, placebo-controlled setting (23). All measure indicated improved sexual responsiveness, and a sexual function questionnaire demonstrated increased sexual arousal, orgasmic completion, and sexual satisfaction.

Vasoactive Medications -- Sildenafil (Viagra)

Phosphodiesterase (PDE-5) inhibitors such as sildenafil (Viagra) effectively treat male erectile dysfunction, but generally have not proven successful in women (24). The best available evidence is a randomized trial of nearly 800 pre- and post-menopausal women with disorders of desire, arousal, orgasm, and/or dyspareunia treated with 10 to 100 mg sildenafil for 12 weeks. Sildenafil was no more effective than placebo in increasing the frequency of enjoyable sexual events or improving any aspect of sexual function (24). However, positive effects of sildenafil on sexual arousal and orgasm have been demonstrated in premenopausal women with SSRI-associated sexual dysfunction. A randomized trial of sildenafil 50 or 100 mg in 98 women with major depression in remission on SSRIs found that sildenafil for eight weeks, compared with placebo, significantly improved scores for global sexual function and orgasmic response (25). Sildenafil use did not impact sexual desire and had no effect and had no effect on hormone levels or measures of depression. Although there have been no studies on the use of other PDE-5 inhibitors, such as tadalafil and vardenafil, on SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction, it is likely that they have similar effectiveness due to their shared mechanism of action. Randomized trial data also suggest that PDE-5 inhibitors may be helpful in treating sexual dysfunction in women with diabetes, multiple sclerosis, or spinal cord injuries (25). Further study is needed in these populations.

Potential side effects of PDE-5 inhibitors include headache, flushing and nausea. These drugs are contraindicated in patients taking nitrates. Patients must be informed that PDE-5 use for women has not been approved by FDA.

Psychotropic Agents

Apomorphine is a dopamine agonist that has been used as a subcutaneous injection for the treatment of Parkinson's disease, and has been researched as an oral agent for arousal disorder. Findings have been inconclusive, and the drug has also been associated with emesis. One small study assessed the effect of apomorphine 3 mg, on both subjective and objective changes in the response cycle of women diagnosed with orgasmic dysfunction. It found that clitoral hemodynamic peak velocities were significantly higher in the medication group, translating into significantly better arousal and lubrication (26). The researchers concluded that apomorphine was beneficial in women with orgasmic problems. Side effects and adverse events were rare, mild, and transient. Although this study was quite small, many sexual health care professionals are optimistic about this provocative drug.

Tibolone

Tibolone is synthetic steroid whose metabolites have estrogenic, progestagenic, and androgenic properties. It has not been approved by the FDA due to concerns about risk of breast cancer and stroke. It is widely used in Europe, but is not currently available in the United States. It has been shown to reduce hot flashes and increase bone mineral density (BMD), and women report that it decreases vaginal dryness and dyspareunia and improves female sexual desire. There are some medical concerns regarding lipid metabolism, hemostasis, and long-term cardiovascular and cancer risks. In randomized trials, tibolone appears more effective than estrogen/progestin therapy for treatment of sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women (27). However, beneficial effects of either of these treatments on sexuality are modest and may not outweigh the risks. Comparative trials of tibolone versus testosterone have not been performed.

Emerging Sexual Therapeutics

Today, the race is on to develop non-hormonal pharmacologic medications for female sexual dysfunction that are safe and effective, with a low side effect profile. A wide variety of oral and topical formulations are under investigation as possible treatment options for female sexual complaints. Most of this work is still preliminary, but it is encouraging that both pharmaceutical researchers and health professionals are now addressing these distressing disorders.

Flibanserin -- It is a 5-HT1A agonist/5-HT2 antagonist, is a promising new drug that may soon be available to treat HSDD. Under investigation worldwide, it is now in Phase 3 trials in the United States. It has demonstrated efficacy with minimal side effects (e.g. nausea, dizziness, fatigue, sleeplessness). Increased bleeding may ensure if flibanserin is used with aspirin or non-steroidal analgesics.

Alprostadil -- It is prostaglandin PGE1, a potent, naturally occurring vasodilator that has been used to treat male erectile dysfunction, and may also have an important role in the regulation of blood flow to the female reproductive tract. It potentiates the activity of sensory afferent nerves, such that local application to the clitoris may increase vaginal vasocongestion, leading to increased physical and subjective sexual arousal. Alprostadil is not currently FDA-approved for the treatment of female arousal dysfunction. Possible side effects include application-site reaction, transient genital pain, lowered blood pressure, and temporary syncope. Randomized, double-blind studies have demonstrated mixed results, and further research is underway (28).

Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone (MSH) -- The MSH analog PT-141 is a melanocortin receptor agonist under investigation for the treatment of female sexual complaints. A small, Phase 2A crossover pilot study examined this medication in premenopausal women diagnosed with arousal disorder, and reported encouraging results. Subjects were treated with placebo or PT-141, 20 mg intranasally, followed by vaginal photoplethysmography to measure blood flow and pulse amplitude and a treatment satisfaction questionnaire. Although there were no changes in blood flow, there were significant changes versus placebo in arousal and desire in the 24-hour period following PT-141 administration.

Phentolamine -- It has been used in oral form and as a vaginal solution to increase sexual arousal. In this study (29) this α-adrenergic blocker in postmenopausal women concluded with inconclusive results and the drug is still under investigation for possible therapeutic effects.

Lasofoxifene -- It is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) that has been formulated to treat osteoporosis, showing bone-sparing and cardio-protective effects without uterine stimulation. It may also be used in breast cancer treatment and adjunctive therapy. It has been shown in some studies to increase BMD and decrease low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, as well as improving sexual function parameters. However, lasofoxifene has not yet been approved by the FDA.

Follow-Up

After initiation of sexual dysfunction, patients should be seen for regular follow-up visits, approximately every three months, until effective interventions are identified and the sexual problem has improved. Patients may then be seen every 6 to 12 months, depending on the potential risks of the treatments selected. Patients using pharmacologic therapeutics will need to be monitored for drug-related risks and side effects at these visits. Treatment efficacy is best assessed by patient self-report of improvement of symptoms.

Sex and Religion

We think of religious people as being faithfully devoted to their beliefs and observances. These beliefs help them order their world, provide meaning to their lives, and offer guidelines for behavior, including sexual activities. Violation of these teachings is therefore considered irreverence for God. Advice or treatment that countermands belief is also viewed as irreverent. Today people enjoy great global mobility. Relocation from one continent to another is far simpler than it was 30 years ago. Along with their families and professions, people bring their spiritual beliefs and practices, which may be as foreign as the names of the towns from which they emigrated. Native residents also may hold spiritual beliefs that are unfamiliar to healthcare providers. Consequently, healthcare providers may be approached by patients of various religious and cultural backgrounds who have questions or concerns about sexuality. Discussing religion with patients may be as discomforting as discussing sexuality. At the same time, it appears that patients would welcome a discussion about religious beliefs and their relationship to health matters under various conditions. In fact, a study in a group of physicians found that personal discomfort with discussion religious topics was the sole multivariate predictor of clinical religious behavior (30). Following four basic principles can help providers to reduce barriers to care and improve outcomes for their religious patients:

- Ask about religious beliefs during the initial visit. A simple question such as "what faith were you raised in?" followed by "Are you still practicing that faith?" will provide sufficient information to go respectfully forward later on if sexual problems are presented. Done in a routine, matter-of-fact fashion, this simple intervention can open doors later on should sexual problems become the focus of treatment for a religiously observant patient.

- Ask about religious teachings regarding sexual behavior. If sexual problems are on patient's agenda, ask about the specific teachings of his or her religion with regard to sexual behavior and specifically, the behavior that is problematic to your patient. An informative source on various sexual matters is the Religious Institute's Denominational Statements resource (31). This online resource contains the official teachings on sexually related issues of many major US religious denominations.

- When in doubt, consult with a religious expert. When working with religiously observant patients, speaking directly with a member of the clergy is the best way to access accurate information about the religion's teachings. Sometimes a consultation is essential, particularly if a patient has misinterpreted doctrine and this poses a barrier to therapy.

- Help couples set reasonable expectations consistent with their beliefs. Religiously observant couples usually do not exist in a world isolated from popular culture. While they may restrict or carefully select the television programs and movies that they will see, a sexualized world is not totally out of their view. There are ways to create reasonable expectations for patients in sex therapy that have value for religious patients of most faiths. One model suggests that therapists discuss sexual interactions with the idea that there are no "ultimates" in sexual interaction. Instead, couples are encouraged to see that sex can vary from encounter to encounter, ranging from very good to mediocre or worse. Therapy focuses on the concept that sexual interactions that produce mutual satisfaction and comfort are a reasonable goal. This varies from couple to couple and from instance to instance. Done with respect for the beliefs and values of the religious couple, this approach can be powerful because it allows each couple to decide what is comfortable for them.

Summary

Female sexual dysfunction is a common problem, affecting about 25% to 63% of all women. Gynecologists have an opportunity to play a central role in the identification and treatment of this often complicated form of dysfunction. Every patient, regardless of the nature of her initial gynecologic complaint, should be screened for female sexual dysfunction. Patients found to have female sexual dysfunction should be referred to a sex therapist for additional screening and counseling. Although treatment options for female sexual dysfunction are still in their infancy, it is important to identify these individuals so that a greater understanding of this common problem can be achieved. Sexual complaints in women take many forms and the etiology is often complex. Diagnosis of female sexual dysfunction is based on a comprehensive history, psychosocial assessment, and physical examination. Treatment is often multidimensional and may encompass several different disciplines. Psychological problems such as depression, anxiety, interpersonal difficulties, current or past sexual abuse, and substance abuse have a negative impact on sexual function and complicate treatment strategies. There are several situations in which referral to a sex therapist can be helpful in treating female sexual dysfunction. Long-standing or lifelong sexual dysfunction is often associated with anger, performance anxiety, and sex-avoidance behaviors and may require counseling. If a patient presents with more than one dysfunction, it may be difficult to identify the initial cause of the sexual problems.

Suggested Reading

- World Health Organization

Measuring Sexual Health: Conceptual and practical considerations and related indicators - National Institutes of Health (NIH)

Sexual Problems in Women

References

- Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA 1999;281:537-544

- Bancroft J, Loftus J, Long JS. Distress about sex: a national survey of women in heterosexual relationships. Arch Sex Behav 2003;32:193-208

- World Health Organization. Measuring sexual health: conceptual and practical considerations and related indicators. WHO (2010)

- Basson R, Berman J, Burnett A, et al. Report of the international consensus development conference on female sexual dysfunction: definitions and classifications. J. Urol 2000;163:888-893

- Kaplan HS. Disorders of Sexual Desire and Other New Concepts and Techniques in Sex Therapy. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel Publications; 1979

- Basson R. Female sexual response: the role of drugs in the management of sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98:350-353

- Sarrel PM. Effects of hormone replacement therapy on sexual psychophysiology and behavior in postmenopause. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2000;9(suppl 1):S25-S32

- Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med 2007;357:762-774

- Bo K, Fincherhagen HB. Vaginal palpation of pelvic floor muscle strength: inter-test reproducibility and comparison between palpation and vaginal squeeze pressure. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2001;80:883-887

- Shifren JL, Monz BU, Russo PA, et al. Sexual problems and distress in United States women. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:970-978

- Dennerstein L, Dudley E, Burger H. Are changes in sexual functioning during midlife due to aging or menopause? Fertil Steril 2001;76:456-460

- Basson R. Clinical practice. Sexual desire and arousal disorders in women. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1497-1506

- Krychman ML. Sexual rehabilitation medicine in a female oncology setting. Gynecol Oncol 2006;101:380-384

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Guidance for Industry. Female Sexual Dysfunction 2000. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/ScienceResearch/SpecialTopics/WomensHealthResearch/ucm133202.htm Retrieved 22 October 2010

- Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med 2007;357:762-774

- Billups KL, Berman LA, Berman JR, et al. A new non-pharmacological vacuum therapy for female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Marital Ther 2001;27:435-439

- Ju YH, Doerge DR, Helferich WG. A dietary supplement for female sexual dysfunction, Avilmil, stimulates the growth of estrogen-dependent breast tumors (MCF-7) implanted in oveariectomized athymic nude mice. Food Chem Toxicol 2008;46:310-315

- North American Menopause Society. The role of testosterone therapy in postmenopausal women: position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2005;12:496-511

- Wierman ME, et al. Androgen therapy in women: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrin Metab 2006;91:3697-3716

- Braunstein GD, Sundwall DA, Katz M, et al. Safety and efficacy of a testosterone patch for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in surgically menopausal women: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1582-1589

- Davis SR, Moreau M, Kroll R, et al. Testosterone for low libido in postmenopausal women not taking estrogen. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2005-2017

- Basson R. Sexuality and sexual disorders in women. Clinical Updates in Women's Health Care 2003;2:1-94

- Segraves RT, Clayton A, Croft H, et al. Bupropion sustained release for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire in premenopausal women. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004;24(3):339-342

- Berman JR, Berman LA, Toler SM, et al. Safety and efficacy of sildenafil citrate for the treatment of female sexual arousal disorder: a double-blind, placebo controlled study. J Urol 2003;170:2333-2338

- Nurnberg HG, Hensley RL, Heiman JR, et al. Sildenafil treatment of women for the antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008;300:395-399

- Bechara A, Bertolino MV, Casabe A, et al. Double-blind randomized placebo control study comparing the objective and subjective changes in female sexual response using sublingual apomorphine. J Sex Med 2004;1:209-214

- Nijland EA, Weijmar-Schultz WC, Nathorst-Boos J, et al. Tibolone and transdermal E2/NETA for the treatment of female sexual dysfunction in naturally menopausal women: results of a randomized active-controlled trial. J Sex Med 2008;5:646-651

- Kielbasa LA, Daniel KL. Topical alprostadil treatment of female sexual arousal disorder. Ann Pharmacother 2006;40:1369-1376

- Robio-Aurioles E, Lopez E. Lopez M, et al. Phentolamine mesylate in postmenopausal women with female sexual arousal disorder: a psycho-physiological study. J Sex Marital Ther 2002;28(Suppl 1): 205-215

- McCord G, Gilchrist VJ, Grossman SD, et al. Discussing spirituality with patients: a rational and ethical approach. Ann Fam Med 2004;2:356-361

- Religious Institute. Denominational Statements: www.religiousinstitute.org/denominational-statements Accessed 28 October 2010

Published: 22 February 2011

Dedicated to Women's and Children's Well-being and Health Care Worldwide

www.womenshealthsection.com