LGBTQ+ Healthcare: Building A Foundation For Better Understanding

WHEC Practice Bulletin and Clinical Management Guidelines for healthcare providers. Educational grant provided by Women's Health and Education Center (WHEC).

LGBTQ, is an abbreviation for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer. There is no single LGBTQ+ community, rather a very diverse population that comes from all racial, ethnic, cultural, socio-economic, and geographic backgrounds. It is very difficult to know the percentage of people who identify themselves, as LGBTQ+. Stigma and the fear of biases contribute to an under-reporting of actual sexual orientation. Some people may also self-identify one way, even if their internal desires or sexual behavior, imply a different orientation. Some LGBTQ+ teens cope with these thoughts and feelings in harmful ways. They may try to hurt themselves. Medical association of LGBTQ+ healthcare practitioners, provides a directory of LGBTQ+ friendly healthcare practitioners. Understanding sexual orientation, gender identity, and sex assigned at birth among the LGBTQ+ community, is imperative in today’s healthcare industry and climate. Children may be born to, adopted by, or cared for temporarily by married couples, non-married couples, single parents, grandparents, or legal guardians, and any of these may be heterosexual, gay or lesbian, or of another orientation. Children need secure and enduring relationships, with committed and nurturing adults, to enhance their life experiences for optimal social-emotional and cognitive development. Scientific evidence affirms that children have similar developmental and emotional needs, and receive similar parenting, whether they are raised by parents of same or different genders.

The purpose of this document is to describe acceptable terms for gender and sexual identity in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ+) patients. It summarizes challenges in the care of the LGBTQ+ population and outlines communication strategies, to provide culturally correct evaluation and treatment of this segment of patients. And explain the cultural competence in the care of LGBTQ+ people.

Women’s Health and Education Center (WHEC) promotes optimal health and wellbeing of all children and all adults. In the United States, public policy related to marriage and family is largely a state function. Consequently, the laws across the country that regulate marriage, adoption, and foster parenting by gay men and lesbians are an inconsistent patchwork. Even civil marriage in a state that permits, it does not ensure access to federal benefits. A core mission of WHEC is, to support the best interests of all children and all adults, regardless of their home or family structure, on the basis of the common principles of justice.

INTRODUCTION

All children need support and nurturing from stable, health and well-functioning adults to become resilient and effective adults. Understanding the history of LGBTQ+ community both in American society and within the profession of psychiatry is essential, in bringing context to the treatment. Some major milestones have contributed to the civil rights of LGBTQ+ people to greater acceptance. First, the Stonewall riots of 1969 have become the historic launching point for gay rights. In 2003, the Supreme Court struck down sodomy laws across the United States (U.S.) with their decision in Lawrence vs. Texas. In 2013, the Supreme Court decision on United States vs. Windsor led to the same sex couple being allowed, to share the same federal benefits as opposite sex couples being allowed to share, ending the Defense of Marriage Act. And in June 2015, the Supreme Court’s decision on Obergefell vs. Hodges led to same-sex marriage becoming legal in all 50 states.

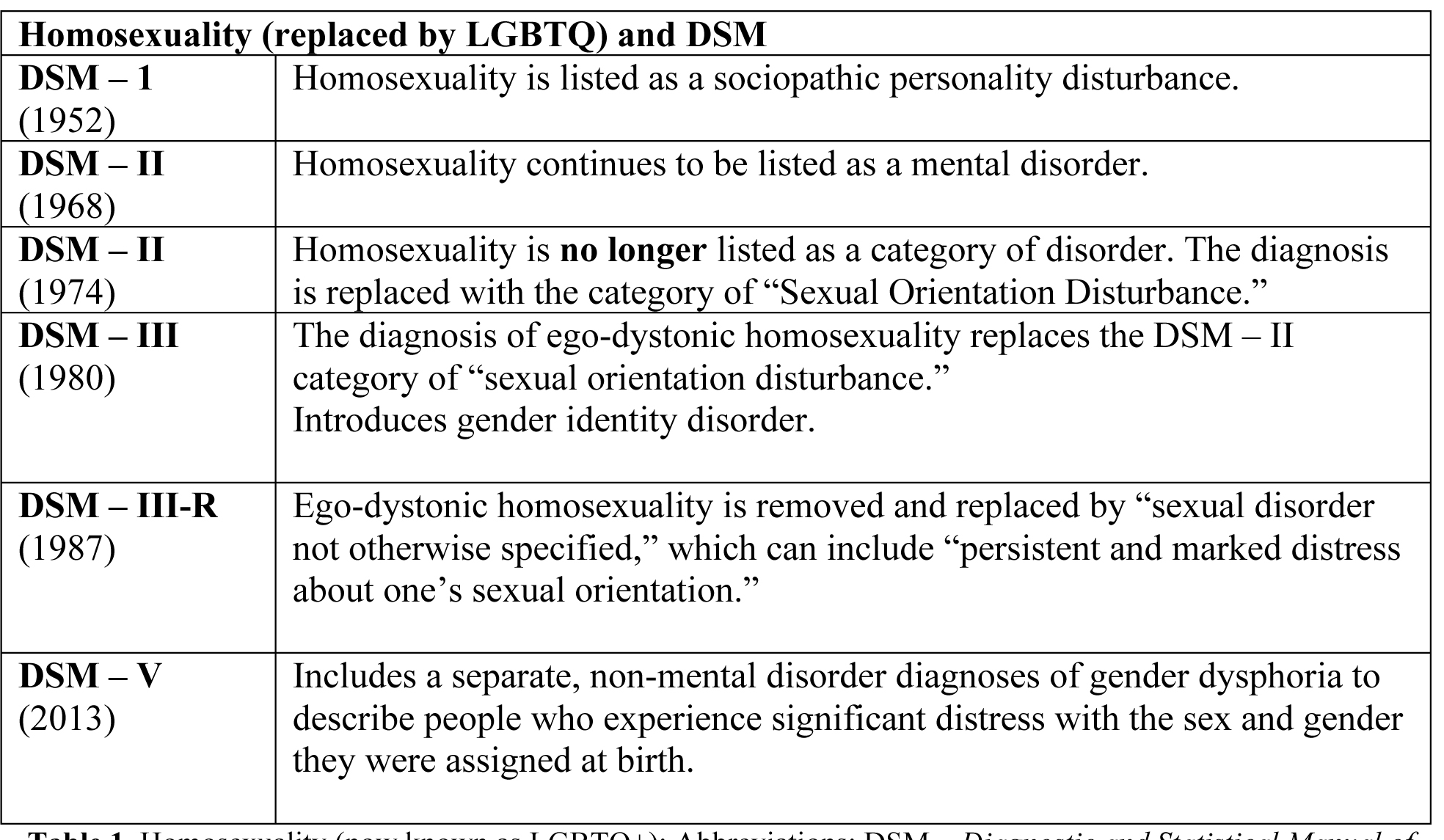

In the context of Psychiatry, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) removed homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), in 1973 based on the new scientific studies, opening the way for new understanding and management of LGBTQ+ patients.

Table 1. Table 1. Homosexuality (now known as LGBTQ+); Abbreviations; DSM - Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; LGBTQ - lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer.

Members of the LGBTQ+ community have unfortunately experienced a challenging history, but health professionals can learn to provide compassionate, comprehensive, and high-quality care with education. Learning to take care of members of this community involves understanding and being open to multiple special considerations and avoiding unconscious and perceived biases.

Size of the LGBTQ+ Population

Data on the proportion of LGBTQ+ people in the U.S. population are sorely lacking. Rough estimates are available, based on the parental reports for children and the number of adults, seeking hormone therapy or surgery at specialty clinics, for the treatment of gender dysphoria. Based on rating on the Child Behavior Check List, 1% of boys and 3.5% of girls reported “wishes to be of opposite sex.” With respect to adults, based on the number of transsexual adults at specialty clinics around the world for treatment of gender dysphoria, the estimated size of the population ranges from 1:2,900 (in Singapore) to 1:100,000 (in United States) for transsexual women; and 1:8,300 (in Singapore) to 1:400,000 (in United States) for transsexual men. However, the number of adults seeking treatment appears to be increasing, and ratio of transgender women to transgender men appears to be decreasing.

HOMOSEXUALITY CONDUCT AS A CRIME,

HOMOSEXULITY AS A DIAGNOSIS

Long before Freud articulated his theory of sexuality, theological doctrine and secular law sought to regulate sexual behaviors and attachment punishments to a variety of sex acts, that were non-procreative or occurred outside of marriage. Proscribed sexual behaviors were often referred to collectively as sodomy, a term that was not clearly defined in most religious and legal texts but included homosexual behavior as well as other non-procreative and extramarital sexual acts. U.S. sodomy laws, which existed in all of the states until 1961, when Illinois eliminated its statute, were the legacy of these prohibitions. Sodomy laws were regularly used to justify differential treatment of sexual-minorities in a variety of arenas, including employment, child custody, and immigration. The expansion of disclosure about sexuality from the domains of law and theology into medicine, psychiatry, and psychology was considered a sign of progress, by many at that time, because it offered the hope of treatment and cure (rather than punishment), for phenomena that society generally regarded as problematic.

After Freud, the division of people into “heterosexuals” and “homosexuals” involved stigmatization of the latter. Many early physicians and sexologists regarded homosexuality as a pathology, in contrast to “normal” heterosexuality, although this view was not unanimous. Freud himself believed that homosexuality represented a less than optimal outcome for psychosexual development, but did not believe it should be classified as an illness. In the 1940s, however, American psychoanalysts broke with Freud, and the view that homosexuality was an illness, soon became the dominant position in American psychoanalysis and psychiatry. Thus, during World War II same-sex behavior, previously had been classified as a criminal offence under military regulations, prohibiting sodomy, the armed services now sought to bar homosexual persons from their ranks. However, many lesbians and gay men served successfully in the military, often with the knowledge of their heterosexual comrades. At the national level, a U.S. Senate committee issued a 1950 report, concluding that homosexuals were not qualified for federal employment, and they represented a security risk because they could be blackmailed about their sexuality.

In 1952, the newly created DSM listed homosexuality as a sociopathic personality disturbance, along with substance abuse and sexual disorders. This classification of homosexuality was used as the basis for laws and regulations, that denied homosexuals employment or prohibited them, from being licensed in many occupations. Many states also passed sexual psychopath laws to criminalize homosexuals as well as rapists, pedophiles, and sadomasochists, in 1987. Many psychiatrists during this time, attempted various “cures” (i.e., attempts to change homosexuals into heterosexuals), including psychotherapy, hormone treatments, aversive conditioning with nausea-inducing drugs, lobotomy, electroshock, and castration.

Meanwhile, some scientific research challenged the illness model. In a landmark study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, directly tested the assumption underlying homosexuality’s inclusion in the DSM, namely, that homosexuality was inherently lined with psychopathology (1991). The conclusion that received extensive support in subsequent empirical research by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), in USA was, homosexuality is not inherently associated with psychopathology, and it is not a clinical entity. This became the consensus view of mainstream mental health professionals in the United States.

Although the AIDS epidemic continues to ravage sexual-minority communities today, some of its long-term consequences are already apparent. Many HIV-positive gay and bisexual men are surviving and thriving today thanks to the development of new HIV treatments. While the AIDS epidemic had considerable impact on individual lives, it also changed the LGBTQ+ community, creating an infrastructure of organizations, dedicated to meeting the health and social needs of LGBTQ+ individuals.

DEFINITIONS

The following terms (from A to Z) will assist the provider in caring for LGBTQ+ patients.Androgyny (gender-fluid, gender-neutral): In between genders, having both male and female characteristics.

Asexual: Individuals that do not experience sexual attraction.

Bisexual (pansexual, queer): Individuals that are attracted to both males and females.

Cisgender: Denoting or relating to a person whose sense of personal identity and gender corresponds with their birth sex.

Cissexism: Prejudice or discrimination against transgender people.

Coming Out: Sharing gender identity publicly.

F2M/FTM (female to male): Female at birth but identifies as a male.

Gay: Identify gender as male but are attracted emotionally, erotically, and sexually to other males.

Gender: Emotional, psychological, and social traits describe an individual as androgynous, masculine, or feminine.

Gender Attribution: Process in which an observer assigns the gender they believe an individual to be.

Gender Binary: Belief that individuals must be one of two genders, male or female.

Gender Expression: Individual appearance, behaviors, dress, mannerisms, speech patterns, and social behavior associated with femininity or masculinity.

Gender Identity: Personal sense of gender that correlates with individually assigned sex at birth or can differ from it.

Gender Non-Conforming: Gender behaviors that are in between feminine or masculine binaries.

Gender Role: Traditional behaviors, characteristics, dress, mannerisms, roles, and traits associated with being male or female.

Gender Queer: Individuals that identify themselves as both feminine and masculine.

Hermaphrodite: A no longer acceptable way of describing intersex individuals.

Heterosexism: Discrimination against gay individuals based on the belief that heterosexuality is the normal sexual orientation.

Heterosexual: Individuals attracted to members of the opposite sex.

Homophobia: Prejudice against the gay community.

Homosexual: Individuals attracted emotionally, erotically, or sexually to members of their own sex. This term has been replaced with lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ+).

In The Closet: Hiding individual gender identity.

Intersex: Individuals born with sexual characteristics that are not typical of male or female binary notions.

Lesbian: Females that are emotionally, erotically, or sexually attracted to females.

LGBTQ: Individuals that are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer.

M2F/MTF (male to female): Male at birth but identifies as a female.

Men Who Have Sex With Men (MSM): Males who participate in sexual relations with other men regardless of sexual orientation.

Queer: A general term refers to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer individuals, sometimes considered derogatory.

Questioning: Individuals uncertain of their gender identity and sexual orientation.

Same-Gender Loving: Bisexual, gay, and lesbian African American individuals.

Sex Assigned At Birth: Sex assigned based on an infant’s external genitalia.

Sexual Behavior: How an individual displays their sexuality.

Sexual Identity: Individual’s description of their sexuality.

Sexual Orientation: Individual’s sexual identity concerning their gender attraction.

Transgender: Individual’s whose gender expression is different from their birth sexual assignment.

Transition: Individual’s psychological, medical, and social process of transition from one gender to another.

Transphobia: Discrimination, harassment, and violence against individuals that do not follow stereotypical gender identities.

Transsexual: A term formally used to describe individuals whose gender identity is different from their assigned birth.

PATIENT vs. PROVIDER USE OF SLANG TERMS

Members of the LGBTQ+ community, in describing their sexual orientation or partners, may use terms such as fag, dyke, gay, homo, or queer. While patients may use these terms, they are considered derogatory when describing a patient by a healthcare providers. The provider and staff should listen to the LGBTQ+ patient and follow their lead, and when in doubt, ask the patient, how they or their partner should be described? Once the terms are established, a note should be made in the record to follow the pattern of description for future visits. Electronic Medical Records (EMRs) may require modification to provide appropriate terminology.

STIGMA AND RISK FACTORS

FAST FACTS

- 38 to 65% of transgender individuals experience suicidal ideation.

- 19 million Americans report that they have engaged in same-sex sexual behavior.

- Three times increased likelihood that lesbian and bisexual women will have a substance use disorder, compared to heterosexual women.

Despite advances in LGBTQ+ rights and acceptance, stigma, both internal and external, continues to be the greatest problem facing sexual and gender minorities. Internally, many LGBTQ+ people develop, and internalized homophobia that can contribute to problems with self-acceptance, anxiety, depression, difficulty forming intimate relationships, and being open about what sexual orientation or gender identity, one actually has. Externally, stigma may be exhibited by the surrounding society and even from withing the LGBTQ+ community. For example, some gay and lesbian people have a difficult time accepting bisexuals. Transgender people have been excluded from some gay organizations, and are only recently received more notice and acceptance throughout the country. Additionally, most LGBTQ+ people are not raised by people who identify as LGBTQ+. Accordingly, they might not have the ability to seek support from parents or peers who may understand these struggles.

LGBTQ+ persons who struggle with higher rates of anxiety, affective disorder related conditions, and substance use disorders most likely have struggled with stigma and the coping with and self-acceptance process. Alarmingly, LGBTQ+ people also have a nearly 3 times higher risk of suicide or suicidal behavior. LGBTQ+ people also face disparities in the physical medical context, including increased tobacco use, HIV and AIDS, and weight-related problems.

LGBTQ+ people are also at greater risk for discrimination, verbal abuse, physical assaults and violence, and perhaps even childhood sexual abuse. Though legal protections have been increasing dramatically, many places do not protect sexual or gender minorities in the workplace, housing, or access to healthcare. Fears of potential discrimination contribute to some LGBTQ+ people not seeking the help they need – medically or psychiatrically – in a timely manner if at all. Studies have shown that many are afraid to be open about their sexual orientation or feelings with their mental health providers.

GENDER AWARENESS, HUMILITY, AND SENSITIVITY

The ways people express their gender can vary. Just like everyone else, transgender people can express their gender through their choice of clothing and style of hair or makeup. Some may choose a name and pronouns that reflect their gender identity. They may openly have their chosen name, and ask others to respect their pronouns (he, she, they, etc.). Some choose to take hormones or have surgeries so that their bodies more closely match their gender identity. Others do not. There is no “right” way to be a transgender person.

Many communities accept LGBTQ+ people without bias. But some communities do not. For adults and teens, hate crimes, job discrimination, and housing discrimination can be serious problems. For teens, bullying in school, talk with your parents or another trusted adults, a teacher, or your principal. Teens who do not feel supported by adults are more likely to be depressed. Some LGBTQ+ teens cope with these thoughts and feelings in harmful ways. They may try to hurt themselves. They may turn to drugs and alcohol. Some skip school or drop out. some run away from home. Lesbian or bisexual girls may be more likely to smoke or have eating disorders.

Telling your parents can be big decision. Help and support in educating parents, family members, and friends about LGBTQ+. If you do not want to talk with your parents, you can talk with a teacher, counselor, doctor, or other healthcare professionals. It is a good idea to ask about what can be kept private, before you talk to a professional. There are also websites, hotlines and resources, at the end of this chapter, where you can be anonymous if you need information.

All teens and adults who are sexually active are at risk of getting a sexually transmitted infection (STI). Many STIs can be passed from one partner to another through oral sex. These STIs include: human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), human papilloma virus (HPV), genital herpes, syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia. Some STIs (HPV and genital herpes) can be transmitted through skin-to-skin contact. HPV also may be spread by contact between genitals and fingers.

Factors That Put LGBTQ+ Patients At Risk For Mental Health

Violence against the LGBTQ+ community has increased over recent years. LGBTQ+ hate crimes are still rising 86% from 2016 to 2021. LGBTQ+ people of color – particularly transgender people – are disproportionately affected by these hate crimes. Challenges abound on the legislative front as well. The White House Administration had made repeated attempts to ban transgender soldiers from serving in the miliary. While these bans have not held up in court, they add to the contentious climate of LGBTQ+ Americans.

- Harassment and discrimination in education: LGBTQ+ students in grades K-12 experience harassment at an alarming rate. About three quarters of LGBTQ+ students report having sexual violence at school. Harassment and assault, especially when it occurs in what should be a safe and supportive setting, can have serious impacts on mental health such as fear, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- Institutional Discrimination: The LGBTQ+ population experiences institutional discrimination in a variety of situations and settings such as the workplace and places of worship. LGBTQ+ individuals are frequently denied carrier advancement or equal compensation compared with their gender-conforming peers, and their unemployment rate is double that of the general population. LGBTQ+ people experience the full gamut of responses from religious organizations, from unconditional support to open hostility. LGBTQ+ people who grew up in religious settings can be especially traumatized by their faith’s rejection or condemnation of homosexuality and non-binary gender identities. Such experiences of discrimination can lead to negative health outcomes such as hopelessness, anxiety, emotional dysregulation, social isolation, and even drug misuse and incarceration.

- Health Disparities: Discrimination in healthcare settings endangers LGBTQ+ people’s lives through delays or denial of medically necessary care. Transgender patients may require medical interventions such as hormone therapy and/or surgery. Despite the presence of guidelines and an advanced transgender medicine treatment paradigm, patients report a lack of providers with expertise in transgender medicine, which is the single largest factor limiting access to care for people who are transgender. Other common barriers such as low income, lack of transportation, and inadequate housing. Because of lack of access to healthcare, transgender patients are at high-risk of negative health outcomes with much higher rates of HIV infection, smoking, drug and alcohol use, and suicide attempts than the general population.

- Family Rejection: It remains all-too common for LGBTQ+ individuals and may negatively affect their both mental and physical health. It may lead to homelessness, which makes it difficult to stay in school or hold a job. Family rejection can also lead to long-lasting psychiatric problems in life. Rejected individuals may develop depression and low self-esteem and may turn to alcohol, cigarettes, or drugs, smoking cigarettes to cope, and attempt suicide.

- History of Trauma: Many individuals in the LGBTQ+ population have experienced past physical assault and harassment. Past trauma compounds any current trauma, exacerbating anxiety about future safety, especially in a political climate that feels hostile.

- Micro-traumas / Micro-aggressions: People who identify as LGBTQ+ often experience brief, subtle expressions of hostility or discrimination. LGBTQ+ people who experience micro-traumas may not meet diagnostic criteria of PTSD, yet suffer tremendously from minority stressors such as from internalized phobia, rejection sensitivity, marginalization, and discrimination both in their personal life and health care settings.

ASSESSMENT AND SCREENING

Understand and Promote Understanding. Healthcare providers should be aware effects of stigma such as prejudice, harassment, discrimination, and violence in lives of LGBTQ+ individuals. Healthcare providers can help reduce stigma by educating the public about LGBTQ+ health issues, policies and by advocating for equal care and equal rights.

- Educate the public with culturally relevant materials from organization such as LGBTQ+ advocacy organizations and provide information through media channels, newspapers, social networking, schools, hospitals, offices, and private companies.

- Educate the medical community by providing instruction to medical students and residents as well as peer supervision to colleague.

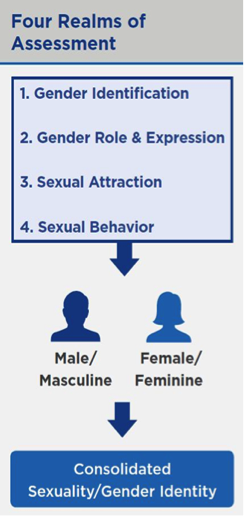

Figure 1. Four realms of assessment and consolidated sexuality and gender identity.

Create an Inclusive Environment. Providers should ensure an inclusive environment by collaborating with LGBTQ+ patients and clients in program design, individual service planning, and the creation of policies and procedures. Policies, procedures, forms, and regulations should be inclusive of LGBTQ+ patients while minimizing re-traumatization. Anti-discrimination and hiring policies as well as well as policies concerning client services should include sexual orientation and gender identity. Employee and client forms should allow LGBTQ+ individuals to answer honestly and thoroughly.

Plan for Continuity of Care. Given the high risk of HIV, suicide attempts, drug and alcohol abuse, and tobacco use among LGBTQ+ people, healthcare providers must determine appropriate levels of care. Providers should consider treatment within their scope of practice; make necessary referrals to integrated clinics; provide a continuum of care referrals for services; and offer services the patient will receive after discharge such as follow-up and monitoring activities, outreach, recruitment, and retention.

Provide Trauma-Informed Care. LGBTQ+ people often experience trauma as gender minorities. Common clinical concerns specific to LGBTQ+ individuals can be addressed by implementing the following principles:

- Understand the impact of identity-based trauma on cognition, emotion, behavior, and perception.

- Provide physical and emotional safety by meeting patient needs, clearly establishing and communicating safety procedures, creating a predictable environment, and fostering respectful relationships.

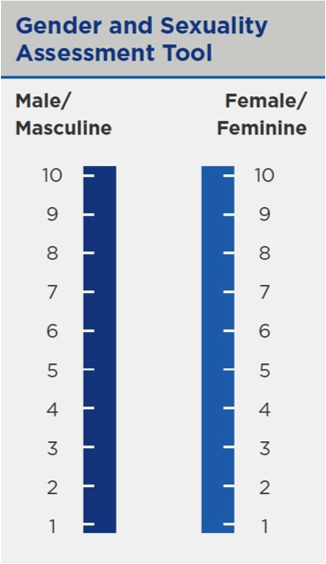

Figure 2. Gender and sexuality Assessment tool.

Despite barriers to work and success, the LGBTQ+ community continues to thrive, and many serve as leaders in the workforce.

BEST PRACTICES & RECOMMENDATIONS

Bridging the divide and creating respectful dialogue, is the way forward. We live in a very divisive world. So much of what we see and hear as part of the socio-political narrative is filled with argument, and contention that polarizes discussion, ideas, and sometimes even people. There are two core principles, “Do No Harm” and “Facilitate Self-Determination” are the foundation. The guidelines that provide context and a rationale for each principle, are listed below. These standards help clinicians promote safety and respect for any client, who might be feeling their way through a complex journey between sexual orientation, gender identity and help de-escalate the divisive discourse around legislative issues.

The Women’s Health and Education Center (WHEC) recommends the following best practices for your work with LGBTQ+ patients:

- With new patients, create an accepting and affirming environment by not assuming sexual or gender identity. Ask: “Do you have sex with men, women or both?” “How do you identify yourself?” We should be sensitive to patients in transition, and ask both how they would like to be addressed as well as use the appropriate pronoun.

- Assess level of openness and self-acceptance; the figure 1, and figure 2 offers a simple visual scale to use in clinical encounters.

- Be aware that there is NO basis for so-called “conversion or reparative” therapy; which are unscientific attempts to change sexual orientation, through shame-based efforts that result in depression, anxiety, and increased suicidal ideation. All major health groups condemn such attempts.

- Be aware that families can be helped to accept their gay or lesbian children and that in turn leads to greatly reduced suicidality and anxiety in such youth given the risk of suicide, be comfortable to ask about risk and resilience factors.

- Healthcare professionals can help the patients with:

- Figure out the best way to talk with patients’ friends and family about the patient’s gender identity;

- Find information and resources in your community;

- Give documents to your school that support your gender identity;

- Get important health care (including vaccines, routine screenings, and birth control);

- Find gender transition care.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES

In addition to incorporating best practices and recommendations, be aware of seven guiding principles for understanding gender and sexuality.

- Gender and sexuality exist in continuum with infinite possibilities.

- The gender and sexuality continuums are separate, yet interrelated realms.

- The gender continuum breaks down into separate, but not mutually exclusive masculine and feminine continuums

- Sexuality is composed of three distinct realms: orientation and attraction; behavior; and identity. These three realms are interrelated but not always aligned.

- Gender may develop based upon biologic sex, but this is not always the case (i.e., transgendered, intersex, androgynous individuals).

- There are biological, psychological, social, and cultural influences at play in gender and sexual development trajectories. Social factors, such as family and peer relationships, robustly shape behavior during preschool and school age years.

- Each individual is unique and composed of multiple identities that exist within and interact with our sociocultural realms, such as socio-economic status, geographic region, race and ethnicity, religious and spiritual affiliation, gender and sexuality among other.

HEALTHCARE FOR TRANSGENDER TEENS

The term transgender has come to be widely used to refer to a diverse group of individuals who cross or transcend culturally defined categories of gender. Most people are told they are a boy, or a girl (male or female) based on the genitals they were born with. This is the sex you are assigned at birth. For some people, that male or female label may not feel right. Someone born female may feel that they are really a male, and someone born male may feel that they are really a female. People who feel this way are called transgender. Others may feel that they belong to neither gender or to both genders. People who feel this way sometimes identify as “gender non-binary,” “gender fluid,” or “gender-queer,” gender-neutral, or agender or gender non-conforming.

Gender Transition Care. It is a process patient can go through to express gender. The way of transitioning include:

- Changing how to dress or act;

- Changing name and preferred pronouns (she, he, they etc.);

- Taking medication (including puberty blockers and hormone treatment);

- Having surgery.

Healthcare professionals can help transition safely. Taking treatment from anyone without a medical license can be dangerous. In most places like United States, permission from parent or guardian to do a hormonal or surgical transition is needed, before the patient is 18 years old. Consultation with mental health professionals and get a letter of support, before starting treatment is highly recommended. This may involve multiple counseling sessions.

How do puberty blockers work?

Puberty blockers (also called suppressors) are medications that delay the changes that come with sexual maturity. These medications can stop menstrual periods and the growth of breasts, or stop the deepening of the voice and the growth of facial hair. Most effects of puberty blockers are reversible. Puberty blockers are given as in hormonal-implant or as a shot. Sometimes it is started when the early stages of puberty are started this include - budding breasts, growing testicles, and light pubic hair.

How does hormone treatment work?

Hormone treatment is medication that helps you look or sound more masculine or feminine. This also may be called cross-sex hormone treatment or gender-affirming hormone therapy. Depending on the treatment, these medications can help you develop sex characteristics, such as:

- Deepening your voice;

- Growing facial hair;

- Developing breasts;

- Changing your body shape.

Most of these changes cannot be reversed. Depending on the hormone, treatment comes in several forms, including as a shot, pill, patch, gel, cream, or implant. Suggested earliest age to wait before the treatment is started is 16 years old, but sometimes puberty blockers can be started in the meantime, if your healthcare professionals recommend it.

Benefits and risks of puberty blockers and hormonal treatment.

Puberty blockers may:

Risks of puberty blockers and hormones treatments are:

- Slow your physical growth and affect your height;

- Decrease the bone density (making the bones more likely to break in future);

- Hormones may increase the risk of – blood clotting problems, high blood pressure, mood changes, and liver inflammation (hepatitis).

Benefits of puberty blockers and hormone treatment are:

Puberty blockers may help the emotional and social development. They may make patients more comfortable in their own bodies. Many studies have shown that hormone treatment is shown to help transgender people with depression and boost self-esteem. These treatments prevent changes in the body that patients are not comfortable with. They also may prevent the need for future surgery, such as removal of breasts (mastectomy).

Both transgender males and females may need to see an obstetrician and gynecologist and other healthcare professionals, such as urologist and psychiatrist during medical transition care and after the transition. Make sure to see an obstetrician and gynecologist if patient has reproductive organs (like a uterus or a vagina), and are taking feminizing hormones (like estrogen).

Gender Affirmation (Confirmation) or Sex Reassignment Surgery

Gender affirmation surgery refers to procedures that help people transition to their self-identified gender. Gender-affirmation options may include facial surgery, top surgery or bottom surgery. Most people who choose gender affirmation surgeries report improved mental health and quality of life. The notion of changing one’s sex through surgery or other means existed well before the term transsexual became commonly used. In the early 20th century, European scientists began to experiment with “sex transformation” with animals and then with humans. In Germany, doctors at Magnus Hirschfield’s Institute for Sexual Science stated performing sex-change operations in 1920s and 1930s. Over time, understanding and acceptance of transgender sex reassignment surgery has grown confirming by a body of research. In 1966, the Johns Hopkins University (U.S.A.) announced its program to perform and evaluate the efficacy of sex reassignment surgery, thus providing professional legitimacy for sex reassignment as a treatment for transsexualism. This was soon followed by similar programs at the University of Minnesota (U.S.A.) and other universities and medical centers in the U.S.A.

Common transgender surgery options include: Facial reconstruction to make facial features more masculine or feminine; Chest or “Top” surgery to remove breast tissue for a more masculine appearance or enhance breast size and shape for a more feminine appearance; and Genital or “Bottom” surgery to transform and reconstruct the genitalia. Surgical management is usually only an option for people over the age of 18 years. One surgery that may be available for teens is mastectomy (removal of breasts).

Surveys report that around 1 in 4 transgender and non-binary people choose gender affirmation surgery. Many insurance companies require patients and or physicians to submit specific documentation before they will cover a gender-affirmation surgery. These documentation includes:

- Health records that show consistent gender dysphoria.

- Letter of support from mental health professionals, such as a social worker or psychiatrist.

DEVELOP HEALTHY RELATIONSHIPS REGARDLESS OF SEXUALITY

Around the puberty and teens years, relationships outside your family become more important. Teens have relationships with their family and friends and will probably interested in romantic or sexual relationship. But healthy relationships do not have to include sex, and or only to the heterosexual sex. Many boys and girls are attracted to members of their own sex during puberty. Some discover that they are gay, lesbian, or bisexual during these years. When deciding whether to have sex, what are some things to consider? Ask yourself what your feelings are about sex? Are you really ready for sex? DO NOT have sex just because: everyone else is; sex will make you more popular; talked into it; afraid the other person will break up with you if you do not; and feel that it will make you a ‘real” man or woman.

A healthy relationship include: Respect; Good communication; Honesty; Independence; and Equality. You feel physically safe in a healthy relationship, and you are comfortable just being yourself. You have other friends and hobbies or interests, and you can enjoy being together and spending some time apart. You and the other person both enjoy the relationship. Consent is an important part of a healthy relationship because it shows respect.

Unhealthy relationships may include the following: Control, such as making all the decisions or keeping you asway from other people, physical abuse, such as pushing or grabbing, hurting, punching or teasing that is mean or makes you feel bad, dramatic statements, and pressure to do things you do not want to do, including sex.

The lack of recognition of marriage between partners of the same-sex has health implications as well. A large body of research has shown that positive health outcomes are associated with marriage. These positive effects are derived in part from the increased social support and relative stability associated with a legally recognized commitment. Denial of legal recognition of marriage between same-sex couples also has a direct impact on LGBTQ+ individuals’ interactions with the healthcare system. In many cases, employer-sponsored health insurance is not extended to same-sex partners, affecting their access to affordable healthcare.

PROTECT TRANSGENDER PATIENTS AND THEIR REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH

In 2010, the U.S. Department of Labor expanded the scope of Family and Medical Leave Act to ensure that employees would be allowed unpaid leave to care for the children of unmarried same-sex partners; however, the act still does not extend this leave to care for unmarried same-sex partners themselves. Some states in U.S. have extended this leave to unmarried same-sex partners, but most have not. In 2010, President Obama issued a memorandum directing the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to adopt regulations requiring all hospitals receiving Medicaid or Medicare dollars to permit visitation by a designated visitor with regard to sexual orientation or gender identity and requiring those hospitals to respect all patient’s advance directives.

PARENTING AND CHILDREN

Before the emergence of visible gay communities in the U.S.A., many lesbian, gay men, and bisexual people married heterosexually for a variety of reasons, including social and family pressures, a desire to avoid stigma, and a perception that such marriages were the only available route to having children. Sometimes individuals have recognized their homosexuality or bisexuality only after marrying a person of the other sex. Many lesbian, gay and bisexual individuals became parents through such marriages. In more recent times, many lesbian, gay and bisexual adults have conceived and reared children while in a same-sex relationship. Other same-sex couples and sexual-minority individuals have adopted children. Data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth indicate that more than 35% of lesbians aged 18 - 44 years had given birth and that 16% of gay men in that age group had a biological or adopted child. Fewer sexual minority than heterosexual individuals are parents, but there are many lesbian mothers and gay fathers in the U.S.A. today.

Thus, many children are currently being reared by one or more sexual-minority parents. The legal status of those parents and of their children varies from state to state. For example, states differ on whether they consider a parent’s sexual orientation to be relevant to custody or visitation in divorce proceedings. In recent years, some states have enacted laws and policies forbidding gay and lesbian individuals or couples from foster-parenting or adopting children; other states have considered laws banning same-sex couples, or all unmarried couples, from foster-parenting or adopting children. A long-standing ban on adoptions by lesbian and gay parents in Florida was overturned in 2010.

Transgender people also can face difficulty in court disputes over custody of their children. Many courts have denied or restricted custody or visitation for transgender parents, or even terminated their parent’s rights, solely because of their gender identity or expression. Only few state courts have held that a parent’s transgender status is irrelevant, absent evidence of harm to the child. Transgender people who have no biological or adoptive relationship to the children they are raising with a partner, face even more difficulties, as they must first convince the court that a person who has raised a child without formal legal or adoptive ties, is nonetheless entitled to custody or visitation.

Women’s Health and Education Center (WHEC) opposes any laws and regulations that discriminate against transgender and gender diverse individuals. It opposes any medically unnecessary restrictions placed on people’s access to reproductive healthcare. Instead, it urges the Administration to eliminate this policy change, to ensure patients have access to quality healthcare they need.

SUMMARY

Lesbian and gay men faced extensive stigma during the World War II era and the years immediately following. Public disclosure of one’s sexual orientation could lead not only to personal rejection and ostracism, but also to unemployment and even arrest, fostering a need for considerable secrecy in one’s daily life. Gay men and lesbians were officially classified as mentally ill. Many were pressured to seek psychiatric treatment to become heterosexual, although interventions purporting to change sexual orientation were generally ineffective. At the same time, emerging gay and lesbian communities and enclaves in large urban centers offered their members the opportunity to meet others who share their sexual orientation. These communities provide a basis for the development of organizational and individual challenges to the stigmatized status of homosexuality.

In the face of rapidly changing cultural views about homosexuality, and recognizing that empirical data to support the illness model was lacking, the American Psychiatric Association’s board of directors voted in December 1973 to remove homosexuality as a diagnosis from the DSM. Their decision was affirmed by a subsequent vote of the Association’s membership. In 1975, The American Psychiatric Association strongly endorsed the psychiatrists’ actions and urged its members to work to eradicate the stigma historically associated with a homosexual orientation.

HIV / AIDS probably changed public perceptions of sexual minorities. As a result of the AIDS epidemic, many heterosexuals began to think about gay men and lesbians in ways that went beyond sexuality: as family members and friends, coworkers, contributors to society, and members of a besieged community. These changes in perceptions of sexual minorities may have contributed to decreases in negative attitudes toward homosexuality that were observed in public opinion polls during the 1990s. While the AIDS epidemic had considerable impact on individual lives, it also changed the LGBTQ+ community, creating an infrastructure of organizations dedicated to meeting the health and social needs of LGBTQ+ individuals.

EDITOR'S NOTE

The Women’s Health and Education Center (WHEC) supports access to all children to:

- Civil marriage rights for their parents, and

- Willing and capable foster and adoptive parents regardless of the parent’s sexual orientation.

The WHEC has always been an advocate for, and has developed policies and information for healthcare professionals, the optimal physical, mental, and social health and wellbeing of all infants, children, adolescents, and young adults. In so doing, the WHEC has supported families in all their diversity, because the family has always been basic social unit in which children develop the supporting and nurturing relationships with adults that they need to thrive.

If two parents are not available to the child, adoption or foster parenting remain acceptable options to provide a loving home for a child and should be available without regard to the sexual orientation of parent(s). Future research is needed to enhance our clinical care of the LGBTQ+ population and their families, including understanding if reduced societal bias actually leads to improved mental health outcomes and if the benefits of marriage as evidenced for opposite sex couples are also manifest in same sex couples. We hope to see a reduction in LGBTQ+ health disparities with increased societal acceptance.

Research Opportunities. Research on the influence of contextual factors (e.g., income, geographic location, race, ethnicity, stigma) on LGBTQ+ health status is lacking. There are many opportunities for future research:

- Large-scale surveys examining the demographic and social characteristics of sexual and gender minorities;

- Patterns of household composition within LGBTQ+ populations, specifically rates of partnership and children with gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender parents;

- Income and education differences among both single and partnered sexual- and gender-minority individuals;

- Impacts of barriers to care – particularly provider knowledge about and attitudes toward LGBTQ+ patients, limited access to health insurance, and discrimination within the healthcare system – on the health of LGBTQ+ individuals; and

- The extent to with LGBTQ+ individuals experience enactments of stigma and the impact of sexual and transgender stigma, at both the personal and structural levels, on LGBTQ+ health.

SUGGESTED READING

- The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Creating Safe Schools for LGBTQ Teens

https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/safe-supportive-environments/PD-LGBTQ.htm - Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network (GLSEN)

Organization supports safe and inclusive schools for LGBTQ students.

https://www.glsen.org/ - LGBT National Youth Talk line

Peer support and resources for LGBTQ teens and young adults.

1-800-246-PRIDE (800-246-7743)

help@LGBThotline.org - PFLAG

Provides confidential peer support, education, and advocacy to LGBTQ+ people, their parents and families, and allies.

https://pflag.org/ - The Gay and Lesbian Medical Association (GLMA)

Health Professionals Advancing LGBTQ Equity

https://www.glma.org/ - World Health Organization (WHO)

Transgender People;

https://www.who.int/teams/global-hiv-hepatitis-and-stis-programmes/populations/transgender-people - United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)

Gay and Lesbian Equality Network (GLEN)

https://healtheducationresources.unesco.org/organizations/gay-and-lesbian-equality-network-glen

Published: 5 August 2022

Dedicated to Women's and Children's Well-being and Health Care Worldwide

www.womenshealthsection.com