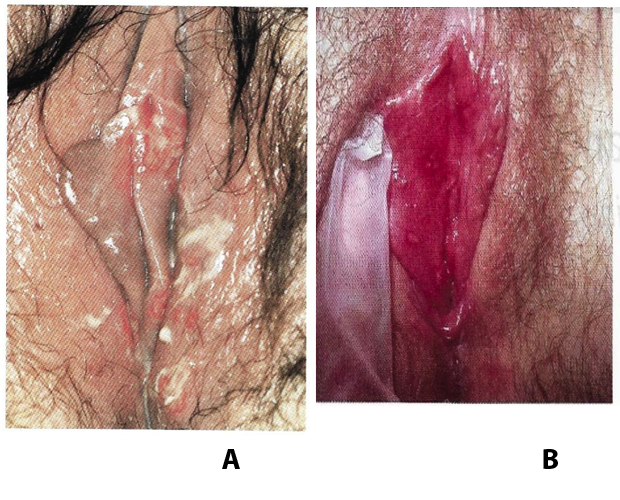

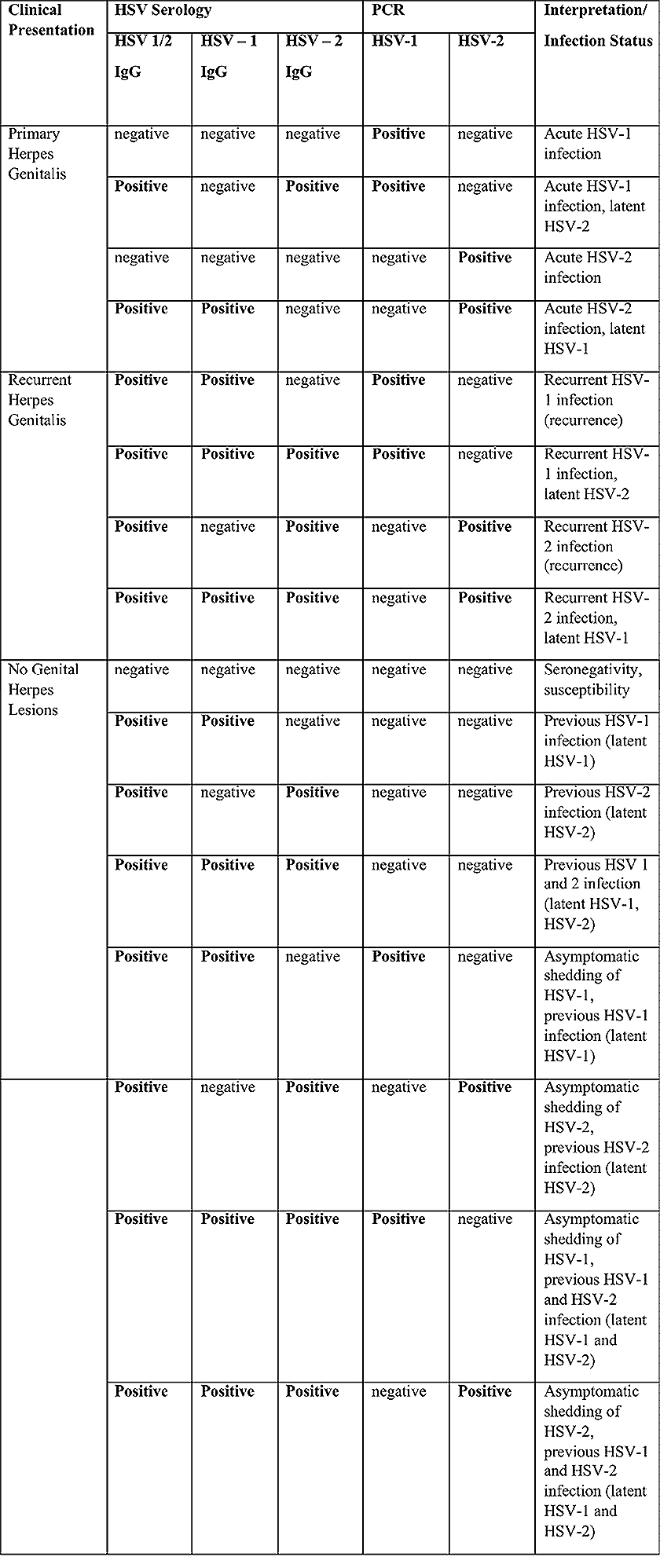

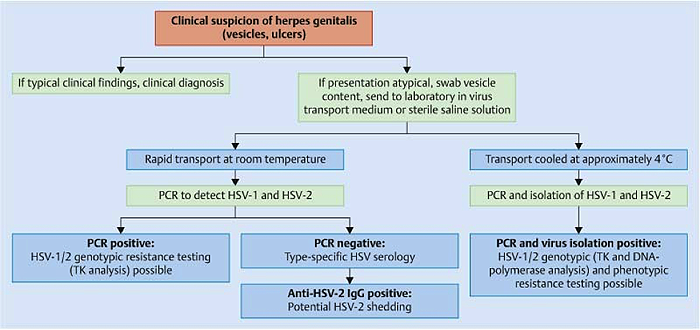

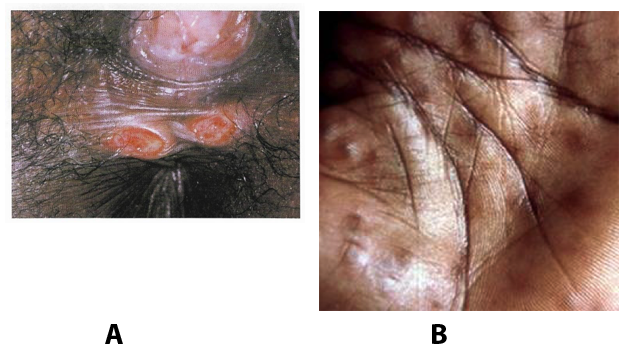

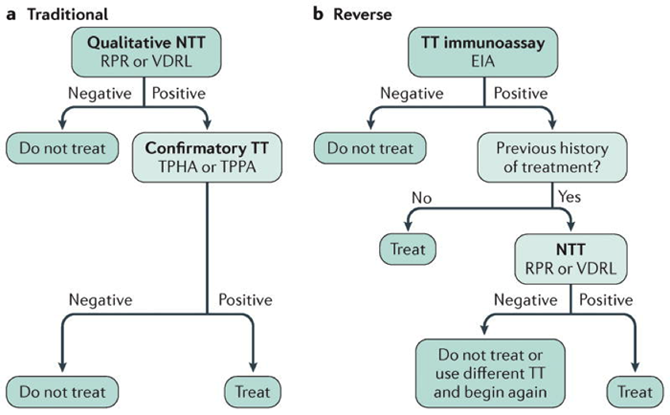

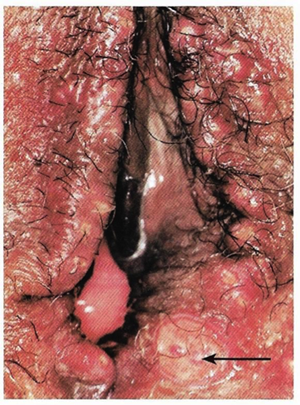

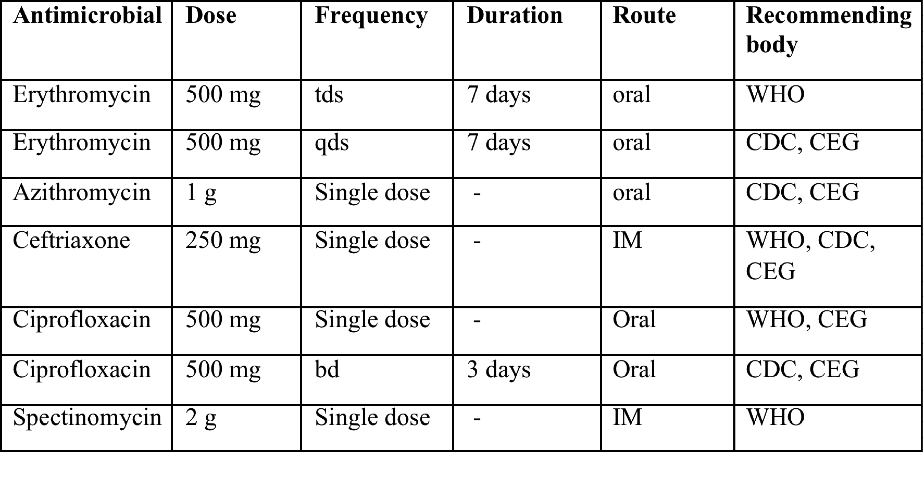

Benignos Vulvar Trastornos de la Piel: Parte 2WHEC Boletín Práctica Clínica y de gestión para proveedores de atención médica. Educación subvención prevista de Salud de la Mujer y el Centro de Educación (WHEC). Vulvar skin disorders include a variety of inflammatory conditions of the vulva that also may affect the extragenital area. Pruritis and pain are two of the most common presenting symptoms in vulvar clinics. Vulvovaginal symptoms often are chronic and can adversely affect sexual function and sense of well-being. The skin functions as a physiologic barrier and a major organ of homeostasis. The practicing obstetrician and gynecologist can play an important role in identifying skin diseases and initiating management. Additionally, the skin often reflects internal disease states. An astute healthcare provider can identify systemic conditions early, with the goal of improving management. The purpose of this document is to provide updated diagnosis and management of the genital ulcers. The following non-infectious vulvar ulcers: vulvar aphthae in adult and pediatric patients, aphthae associated with Behҫhet's disease, vulvar ulcers resulting from Crohn's disease are discussed. Genital ulcers because of common sexually transmitted diseases discussed are herpes simplex, syphilis, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), granuloma inguinale (Donovanosis), vulvar ulcers associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. A. Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs) Characterized by Genital UlcersThe most common infectious etiologies of genital ulcer disease in the United States, in descending order of incidence are herpes simplex virus (HSV), syphilis, and chancroid. Less frequent causes of genital ulcers in the United States are HIV infection, LGV and granuloma inguinale. I. Genital HerpesHerpes genitalis is caused by the herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) or type 2 (HSV-2) and can manifest as primary or recurrent infection. It is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections and due to associated physical and psychological morbidity it constitutes a considerably, often underestimated medical problem. Both organism, HSV-1 and HSV-2 are enveloped DNA viruses that are sensitive to disinfectants and environmental factors (1). Due to marked genetic homology between HSV-1 and HSV-2 numerous biological similarities and antigenic cross- reactions between viruses exist. Type-specific epitopes include the viral glycoprotein (g) gG (HSV-1 and HSV-2) and gC (HSV-1) (1). Mode of transmission: the primary mode of both HSV-1 and HSV-2 is through direct contact. Genital HSV-2 infection is associated with an increased risk of HIV infection (2). Primary genital infections with HSV-1 and HSV-2 are usually asymptomatic. The classical clinical features consist of macular or popular skin and mucous membrane lesions occurring approximately 4-7 days after sexual contact; these progress to vesicles, pustules and ulcers. It can last for up to 3 weeks. Typical symptoms also include pain, especially painful inflammatory swelling of the vulva in women, burning pain and dysuria. Lymphadenopathy, fever and cervicitis (in women) / proctitis (in men) are relatively common associated symptoms. Genital herpes may manifest atypically, particularly in the female genital tract, such as a solitary lesion and fever, making the clinical diagnosis far more difficult. Signs of herpes lesions of the cervix are relatively common in the absence of symptoms, while urethral manifestations are often associated with severe micturition problems.  Recurrent herpes genitalis follows the primary eruption the virus establishes lifelong latency in sensory neural ganglions; in the case of primary genital infection the sacral ganglions are mainly involved. From here the virus can reactivate, causing recurrent infection. Recurrences occur in almost every person suffering symptomatic primary herpes genitalis due to HSV-2, in a third of patients frequently (at least 6 times a year). Recurrent HSV-1 infections occur over 5 times less commonly (3). Asymptomatic genital viral shedding: In the majority of cases endogenous viral reactivation is characterized by asymptomatic genital viral shedding. Most commonly HSV-2 is shed by HSV-2 seropositive patients, and this is the case for almost anyone who is anti-HSV-2 IgG positive (4). In contrast, HSV-1 shedding is uncommon. These data allow the assumption, with a high level of certainty, that HSV-2 seropositive people should always be regarded as potential virus excretors. Both primary and recurrent HSV infection in pregnant women can result in intrauterine viral transmission and congenital HSV infection, although the incidence is low at just 5% of all HSV infections in newborns (5). Summary of virology and serology findings for the laboratory diagnosis of HSV infections with or without genital lesions and for asymptomatic viral shedding is provided in the table 1 below (6).  Summary of the recommended viral diagnostic algorithm for herpes genitalis Antiviral TherapyStandard first-line drugs include acyclovir, valacyclovir and famciclovir. The specific antiviral action of these acyclic nucleoside analogues is based on their phosphorylation to monophosphate form by thymidine kinase (TK), the key enzyme of HSV-1 and HSV-2, with subsequent phosphorylation via di- to tri-phosphate form by cellular enzymes (7). Primary herpes genitalis Valacyclovir: 2 x 500 mg by mouth daily, for 7 - 10 days. Severe primary herpes genitalis Primary herpes genitalis during pregnancy Recurrent herpes genitalis (5 - 6 episodes per year) Valacyclovir: Famciclovir: Mild presentations can also be treated topically with acyclovir or foscarnet. This not adequate during pregnancy. In immunocompromised patients (e.g. HIV) higher doses, longer treatment periods and acyclovir IV may be necessary. Recurrent herpes genitalis during pregnancy Preventive treatment before pregnancy Prophylaxis / viral suppression (>5 – 6 episodes per year) Valacyclovir: 1 x 500 mg by mouth daily, maximum 6 months. According to a Cochrane study (8), viral suppression / prophylaxis may already be indicated after at least 4 recurrences per year. Longer than 6 months in certain settings (e.g. HIV). Prerequisite for viral suppression / prophylaxis: monthly renal and liver laboratory parameters. Recurrent herpes genitalis with acyclovir II. SyphilisTreponema pallidum subspecies pallidum (T. pallidum) causes syphilis via sexual exposure or vertical transmission during pregnancy. The spirochete has a long latent period during which patients have no signs or symptoms but can remain infectious.  Transmission and Dissemination Transmission of venereal syphilis occurs during sexual contact with an actively infected partner; exudate containing as few as 10 organisms can transmit disease (9). Spirochetes directly penetrate mucous membranes or enter through abrasions in skin, which is less heavily keratinized in peri-genital and peri-anal areas than skin elsewhere. Once below the epithelium, organisms multiply and begin to disseminate through the lymphatics and bloodstream. The infection rapidly becomes systemic, if untreated. Profuse spirochetes within the epidermis and superficial dermis in secondary syphilitic lesions enable tiny abrasions created during sexual activity to transmit infection (10). Penetration of the blood-brain barrier, occurring in as many as 40% of individuals with untreated syphilis, can cause devastating neurological complications (11). Neurosyphilis is typically described as a late manifestation but can occur in early syphilis. Symptomatic manifestations of neurosyphilis include chronic meningitis, meningovascular stroke like syndromes and manifestations common in the neurological forms of tertiary syphilis (namely, tabes dorsalis and general paresis, a progressive dementia mimicking a variety of psychotic syndromes) (11). Diagnosis, screening and prevention A syphilis diagnosis is often based on a suggestive clinical history and supportive laboratory (that is, sero-diagnostic) tests. The classically painless lesions of primary syphilis can be seen on the sites of exposure. Sometimes can be missed, especially in hidden sites such as the cervix and rectum.  Serological testing has become the most common means to diagnose syphilis whether in people with symptoms of syphilis, or in those who have no symptoms but are detected through screening. A limitation of all syphilis serological tests is their inability to distinguish between infection with T. pallidum subsp. Pallidum and the non-venereal T. pallidum subspecies that cause yaws, pinta or bejel. Definitive Diagnosis by Direct Detection: The choice of method for diagnosing syphilis depends on the stage of disease and the clinical presentation. In patients presenting with primary syphilitic ulcers, condyloma lata (genital lesions of secondary syphilis) or lesions of congenital syphilis, direct detection methods – which include darkfield microscopy, fluorescent antibody staining, immunohistochemistry and PCR (polymerase chain reaction), may be used to make a microbiological diagnosis. However, with the exception of PCR, these methods are insensitive and require fresh lesions from which swab or biopsy material can be collected as well as well-experienced technologists. T. pallidum PCR is a developing technology that is still primarily available in research laboratories, although these tests are anticipated to be more widely available in the near future. Recent research indicates that this technology may be helpful for the diagnosis of neurosyphilis by the detection of T. pallidum DNA in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with syphilis, particularly among HIV-infected individuals (13). Global Estimates of Prevalence  WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Syphilis (15):Early syphilis Remarks: Doxycycline is preferred over ceftriaxone due to its lower cost and oral administration. Doxycycline should not be used in pregnant women. Azithromycin is on option in special circumstances only when local susceptibility to azithromycin is likely. If the stage of syphilis is unknown, recommendations for people with late syphilis should be followed. Late syphilis Remarks: the interval between consecutive doses of benzathine penicillin should not exceed 14 days. Doxycycline should not be used in pregnant women. Congenital syphilis Remarks: if an experienced venipuncturist is available, aqueous benzyl penicillin may be preferred instead of IM injections of procaine penicillin. Pregnant Women (early syphilis) Remarks: although erythromycin and azithromycin treat the pregnant women, they do not cross the placental barrier completely and as a result the fetus is not treated. It is therefore necessary to treat the newborn infant soon after delivery. Ceftriaxone is an expensive option and is injectable. Doxycycline should NOT be used in pregnant women. III. ChancroidChancroid is a sexually transmitted disease caused by the Gram-negative bacterium Haemophilus ducreyi. It is characterized by necrotizing genital ulceration which may be accompanied by inguinal lymphadenitis or bubo formation.  H ducreyi is a fastidious organism which is difficult to culture from genital ulcer material. DNA amplification techniques have shown improved diagnostic sensitivity but are only performed in few laboratories (16). The management of chancroid in the tropics tends to be undertaken in the context of syndromic management of genital ulcer disease and treatment usually with erythromycin. A number of single dose regimens are also available to treat H ducreyi infection. Genital ulceration as a syndrome has been associated with increased transmission of HIV infection in several cross sectional and longitudinal studies. Effective and early treatment of genital ulceration is therefore an important part of any strategy to control the spread of HIV infection in tropical countries. Recommended treatment regimens for chancroid from the WHO, CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) and the United Kingdom Clinical Effectiveness (CEG)  Other Management Issues Fluctuant buboes should be aspirated in order to provide symptomatic relief and to avoid the further complication of spontaneous rupture. Incision and drainage of fluctuant buboes, with subsequent packing of the wound, has also been recommended as an effective management strategy of chancroid and avoids the need for frequent bubo re-aspiration. In countries where the practice of syndromic management is adopted, patients with genital ulcers should receive treatment for both chancroid and syphilis. Therapy for granuloma inguinale should be added to the regimen in endemic areas and treatment for lymphogranuloma venereum should be given if inguinal buboes are present. Patients with genital ulcers should be seen after treatment to ensure that healing has occurred, to exclude the possibility of reinfection, and to ensure that partner notification has taken place. All patients with genital ulcers should receive appropriate health education and safer sex practices should be discussed. Serological screening for both syphilis and HIV infection should be offered at the time of genital ulcer presentation and again after 3 months at the end of the window period for both diseases. IV. Lymphogranuloma Venereum (LGV)Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is a sexually transmitted disease caused by L1, L2 and L3 serovars of Chlamydia trachomatis that primarily infects the lymphatics. In the last 10 years outbreaks have appeared in North America, Europe, and Australia in the form of proctitis among men who have sex with men. Three stages have been described: First stage (primary LGV): The incubation period lasts 3 – 30 days, after which a primary lesion occurs in the form of a small papule, pustule, nodule, shallow erosion, or herpetiform ulcer. The initial lesions may be differentiated from the more common herpetic lesions by the lack of pain associated with the lesion. The primary lesion of LGV is most commonly located on the coronal sulcus of men and on the posterior vaginal wall, fourchette (known as the frenulum of labia minora/posterior commissure of labia minora) or vulva and on the cervix of women. The lesion usually heals within 1 week and may go unnoticed in the urethra, vagina, or rectum. Differentiation from a syphilitic chancre requires serologic testing. Secondary lesions (secondary LGV): It begins within 2-6 weeks after the onset of primary lesion. Depending on the site of inoculation. LGV can cause inguinal syndrome (after primary lesion of the anterior vulva, penis, or urethra) or anorectal syndrome (usually after primary lesion of the posterior vulva, vagina, or anus). When both inguinal and femoral lymph nodes are involved, they can be separated by the inguinal (Poupart's) ligament, "Groove sign." This sign is pathognomonic of LGV but occurs in only 15% - 20% of cases (17). The systemic spread of LGV C. trachomatis may be associated with low-grade fever, chills, malaise, myalgias, and arthralgias. In addition, systemic spread occasionally results in arthritis, pneumonitis, abnormal hepatic enzymes, and perihepatitis. Rare systemic complications include cardiac involvement, aseptic meningitis, and ocular inflammatory disease. In the rare pharyngeal syndrome affecting the mouth and throat, cervical lymphadenopathy and buboes can occur.  Tertiary stage (third-stage LGV, genito-anorectal syndrome): This stage manifest predominantly in women, but also in homosexual men, because of the location of the involved lymphatics. It is characterized by a chronic inflammatory response and the destruction of tissue, which is followed by the formation of perirectal abscess, fistulas, strictures, and stenosis of rectum. Lymphorroids are hemorrhoids-like swellings of obstructed perirectal, and intestinal lymphatics may also occur. If it is not treated, chronic progressive lymphangitis leads to chronic edema and sclerosing fibrosis. This results in strictures and fistulas that can cause elephantiasis of the genitals, esthiomene (chronic ulcerative disease of vulva leading to disfiguring fibrosis and scarring), and frozen pelvis syndrome. Diagnosis Modern techniques now rely on nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) in well-equipped laboratories (18). The assays have high sensitivity and specificity. For the detection of LGV serovars of C. trachomatis different DNA samples can be used: 1) primary anogenital lesion swab (ulcer base exudate), 2) rectal mucosa swab (when anorectal LGV is suspected), or 3) enlarged or fluctuant lymph nodes or buboes aspirate (when inguinal LGV is suspected. The second step diagnostic test is performed only if the first step test detects C. trachomatis in the sample. The second step diagnostic test in LGV biovar-specific DNA NAAT from the same sample used in the first step test. Two tests for the second step are available: a real-time PCR-based test and a real-time quadriplex PCR-based assay. Both PCR techniques are reliable; the assay correctly identified 100% of non-LGV chlamydial specimens, 100% with no chlamydial infection, and 96.36% LGV specimens (19). Histology of lymph nodes is not specific: follicular hyperplasia, abscesses, cryptitis and crypt disease abscesses without distortion of crypt architecture. Management Recommended treatment regimens for LGV (20)  As adjunctive therapy, the aspiration of fluctuant buboes is recommended for pain relief and prevention of rupture or chronic sinus formation, in contrast to surgical incision of buboes due to potential complications. The pharynx is a reservoir for chlamydia and LGV and may play a role in ongoing transmission. Although spontaneous clearance may occur in untreated patients with pharyngeal chlamydia, in high-risk STD clinic patients, testing the pharynx for chlamydia should be considered. V. Granuloma inguinale (Donovanosis)Granuloma inguinale is a genital ulcerative disease caused by the intracellular gram-negative bacterium Klebsiella granulomatis. The disease occurs rarely in the United States, although it is endemic in some tropical and developing areas, including India, Papua, New Guinea, the Caribbean, central Australia, and southern Africa (21). Clinically, the disease is commonly characterized as painless, slowly progressive ulcerative lesions on the genitals or perineum without reginal lymphadenopathy; subcutaneous granulomas (pseudobuboes) also might occur. The lesions are highly vascular (i.e., beefy red appearance) and bleed. Extragenital infection can occur with extension of infection to the pelvis, or it can disseminate to intra-abdominal organs, bones, or the mouth. The lesions also develop secondary bacterial infection and can coexist with other sexually transmitted pathogens.  Diagnostic Considerations The causative organism of granuloma inguinale is difficult to culture, and diagnosis requires visualization of dark-staining Donovan Bodies on tissue crush preparation or biopsy. No FDA-cleared molecular tests for the detection of K. granulomatis DNA exist, but such an assay might be useful when undertaken by laboratories that have conducted a CLIA verification study. Tissue biopsy and Wright-Giemsa stain are used to aid in the diagnosis. The presence of Donovan bodies in the tissue sample confirms donovanosis. They were discovered by Charles Donovan. Donovan bodies are rod-shaped, oval organisms that can be seen in the cytoplasm of mononuclear phagocytes or histocytes in tissue samples from patients with granuloma inguinale.  Treatment Several antimicrobial regimens have been effective, but only a limited number of controlled trials have been published (21). Treatment has been shown to halt progression of lesions, and healing typically proceeds inward from the ulcer margins; prolonged therapy is usually required to permit granulation and re-epithelialization of the ulcers. Relapse can occur 6-18 months after apparently effective therapy. Recommended Regimen (CDC): Alternative Regimens(CDC): The addition of another antibiotic to these regimens can be considered if improvement is not evident within the first few days of therapy. Addition of an aminoglycoside to these regimens is an option (gentamicin 1 mg/kg IV every 8 hours). Other management considerations: Persons should be followed clinically until signs and symptoms have resolved. All persons who receive a diagnosis of granuloma inguinale should be tested for HIV and syphilis. VI. HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus)-associated Vulvar UlcerNumerous observational studies have reported an association between genital ulcer disease (GUD) and an increased risk of HIV acquisition in HIV-negative individuals (22). It is plausible that, in and HIV-negative , GUD might increase susceptibility to HIV infection by disrupting the mucosal barrier and by inflammatory changes, which increase recruitment of HIV target cells to the ulcer. To assess the timing of symptomatic GUD relative to HIV seroconversion, in this study (22), concluded prevalence of GUS was increased among case subjects, at visit 2 and HIV load was increased in HSV-2 seropositive case subjects, compared with that in HSV-2 seronegative subjects, at 5 and 15 months after seroconversion. HIV acquisition is associated with HSV-2 seropositivity, and GUD is increased after seroconversion. HIV load is increased in HSV-2 positive subjects who seroconverted, suggesting a role for treatment of HSV-2 infection in HSV-2 infection in HSV-2 seropositive, dually infected individuals.  Symptomatic GUD is increased as a consequence of HIV acquisition, probably as a result of reactivation of pre-existing HSV-2 infection. Also, there is evidence that HSV-2 up-regulates HIV load and causes GUD, suggesting a role of treatment/prophylaxis of HSV-2 infection in individuals at risk for HIV and in newly HIV-infected individuals. Most studies examining HIV-associated ulcers are conducted in Africa and involve the risk of transmission and co-infection with herpes simplex, syphilis, or chancroid. HIV-associated ulcers on vulva and genitals are similar to ulcers that affect the oral mucosa, esophagus, and rectum in these patients, and pathogenesis typically may be the same.  HIV-associated ulcers are typically large, painful, and recurrent. Patients are generally severely immunocompromised with a low CD4 count and AIDS-defining infections. The pathogenesis of HIV-associated ulcers remain unknown. Immunosuppression, altered host response and direct infection by HIV are proposed etiologies. In support of these theories is the fact that the CD4 count is typically low, and some women respond to antiretroviral therapy. Local destruction by non-healing ulcers can be severe, with formation of a recto-vaginal fistula reported and a labial-vaginal fistula extending to the ischiorectal fossa. Although biopsies are usually non-diagnostic, obtaining one as part of evaluation is nevertheless recommended in patients with HIV-associated ulcer both to rule out malignancy and as a method of searching for potentially treatable infectious causes such as CMV, HSV, and mycobacterial infections. All women presenting with HIV-associated ulcers should additionally be screened for HSV and syphilis. Screening for chancroid, LGV and granuloma inguinale in select patients with high-risk behavior or from endemic regions is also prudent. Early identification and treatment of HIV-associated vulvar ulcers are essential given the potentially crippling sequalae. Variably favorable response typically is seen with either topical, intralesional or oral corticosteroids (23). High-dose corticosteroids are reported to promote healing of individual patients, although the ideal dosing regimen has not yet been studied. Antiviral therapy with acyclovir is not beneficial (23). Given use of thalidomide for the treatment of complex aphthosis and aphthae of Behҫhet's disease (BD), this drug has been used to treat HIV-associated ulcers. The largest trial is a randomized controlled trial of treatment group received 200 mg/day of thalidomide. After 4 weeks of treatment, 55% of these patients had complete healing of ulcers compared with only 7% of the placebo group (23). B. Non-Infectious Vulvar UlcersUlcers should be differentiated from erosion both clinically and histologically. This is accomplished on the basis of depth. An erosion is a defect in the epidermis only, resulting in a red, smooth, moist, superficial, atrophic plaque. Ulcers are deeper, extending into the underlying dermis, and appear necrotic at the base with either yellow, fibrinous material or an eschar (a dry scab) adherent to it. Large, deep, and long-standing ulcers heal with scarring, while erosions and superficial ulcers typically heal without scarring. Non-infectious ulcers include those caused by drug reactions or adverse effects, autoimmune or inflammatory disease, trauma, and aphthous ulcers. I. Aphthous Ulcers Oral aphthae (aphthosis, aphthous stomatitis, recurrent aphthous ulcers) have similar characteristics to vulvar aphthae. Commonly known as canker sores, they are painful, recurring lesions of the oral mucous membranes. This is the most common lesion affecting oral mucosa; occurring up to 20% of the general population and 60% of select group (24). They are typically very tender and can become painful enough to interfere with speech, mastication, or swallowing. Both oral and vulvar aphthae have been classified into three groups; Aphthae are classified further based on clinical course: |