Uterine Myomas: A Comprehensive ReviewDr. Edward E. Wallach

Professor of Gynecology and Obstetrics

Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics

The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions

Baltimore, Maryland (USA)Uterine leiomyomata are among the most frequent entities encountered in the practice of gynecology. It occurs in 20-40% of women during their reproductive years. Approximately 600,000 hysterectomies are performed per year in the United States for uterine myomas. Many surgical procedures other than hysterectomy are also commonly performed to deal with myomas. The purpose of this document is to review the literature and medical and surgical advances in the management of uterine myomas. We hope this helps healthcare providers the decision-making process as logical as possible.Uterine leiomyomata are referred to interchangeably as myomas, fibroids, fibromyomas, leiomyofibromas, and fibroleiomyomas. Because the tumor consists of uterine smooth muscle as well as fibrous tissue, the term fibroid does not adequately capture the nature of the lesion. For the sake of simplicity, this report will use the term myoma. Background: Uterine myomas are benign tumors that originate from smooth muscle cells of the uterus, although in some cases the smooth muscle of uterine blood vessels may be their source. Myomas range in size from seedlings to large uterine tumors. They may be solitary or multiple and can be found within the myometrium (intramural), externally extending to the serosa (subserous), or internally impinging on the uterine cavity (submucous). Myomas may also be pedunculated and extend through the internal os of the cervix. Myomas are estrogen-dependent tumors. Their growth is clearly associated with exposure to circulating estrogen. They exhibit maximum growth during a woman's reproductive life when estrogen secretion is maximal. Myomas decrease in size during menopause and under other hypo-estrogenic conditions. Myomas grow during pregnancy, a phenomenon that may be caused by estrogens, but also by increased blood flow and edema. They bind 20% more estradiol (E2) per milligram of cytoplasmic protein than normal adjacent myometrium. Growth patterns and locations within the uterus appear to be the major determinants of the clinical manifestations of myomas. Signs and Symptoms: Most patients with uterine myomas are symptom free. When symptoms occur, they usually correlate with the location of the myomas, their size, or concomitant degenerative changes. Excessive menstrual bleeding, attributed to vascular alterations of the endometrium, is often the only symptom produced by myomas. The increased size of the uterine cavity and the surface area of the endometrium also contribute to increasing the quantity of menstrual flow. A dysregulation of local growth factors and aberrant angiogenesis has also been implicated in the abnormal bleeding patterns observed in women with myomas. Pain, as a symptom of myomas, is relatively infrequent. It is usually associated with the torsion of the pedicle of a pedunculated myoma, cervical dilatation by a submucous myoma protruding through the lower uterine segment, or degeneration associated with pregnancy. In these conditions, pain could be acute and requires immediate attention. Adenomyosis is frequently found in patients with myomas, and diffuse adenomyosis may be the cause of pain and heavy bleeding. Pressure symptoms and increased abdominal girth are more commonly encountered than pain. As myomas grow, pressure is exerted on adjacent viscera with manifestations from the urinary tract, such as frequency, outflow obstruction, and compression of ureter. Gastrointestinal symptoms such as constipation or tenesmus may be the result of a posterior wall myoma that is exerting pressure on the recto-sigmoid. Infertility is rarely caused by myomas, but when it is, it is associated with a submucous myoma or a markedly distorted, enlarged endometrial cavity that interferes with normal implantation or with sperm transportation. Severe displacement of the cervix is also capable of adversely affecting sperm deposition at the cervical os. Intramural myomas may cause obstruction or dysfunction of the tubal ostia or intramural portion of the tubes. For patients undergoing in-vitro fertilization, distortion of the endometrial cavity by myomas is associated with decreased pregnancy rates and spontaneous abortion rate up to 50% of cases. Uterine myomas have also been implicated in recurrent pregnancy loss. Malignant transformation of myomas is extremely rare. It is felt that leiomyosarcomas arise de novo and may be unrelated to benign leiomyomata. Because malignancy in association with myomas is rare, careful consideration must be given to specific indications for performing surgery. A history of rapid growth, for example, an increase in uterine size by 6 weeks in a year, especially postmenopausal growth, should prompt resection of the tumor(s), even in the absence of associated symptoms. Diagnosis: Myomas often remain constant in size for many years. Ultrasound examination also assists in documenting growth of myomas with a finer level of discrimination than that obtained by serial pelvic examination. Intravenous pyelography may be occasionally necessary to define renal and ureteral characteristics when ureteral distortion is strongly suspected. Magnetic resonance imaging provides better discrimination of the source of a pelvic mass. Regardless of imaging procedures, in the event of diagnostic uncertainty, surgical exploration may be required. Hysterosalpingography (HSG) or sonohysterography are especially effective in evaluating the contour of the endometrial cavity and patency of the fallopian tubes in infertility patients.

Hysterosalpingogram demonstrating a large filling defect caused by a solitary submucous myoma before hysteroscopic resection.

|

Hysterosalpingogram provides the outline of a normal uterine cavity. Spillage of the contrast media through the left fallopian tube outlines the circumference of a large pedunculated myoma originating from the left lateral uterine wall.

| Management: Most myomas produce no symptoms and careful observation is suitable management for most myomas. They are mostly confined to pelvis and are rarely malignant. The choice of approach should be predicted upon careful consideration of many factors, both medical and social, including age, parity, childbearing aspirations, extent and severity of symptoms, size and number of myomas, location of myomas, associated medical condition (s), possibility of malignancy, proximity to menopause, and desire for uterine preservation. Medical Management: Hormonal therapy usually consists of progestational agents and Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Analogues (GnRHa). Norethindrone, medrogestone, and medroxyprogesterone acetate have been successfully used to achieve diminution in aggregate size of the myomatous uterus. Progestational compounds may also exert a direct antiestrogenic effect at the cellular level. However, evidence that the antiprogesterone mifepristone decreases myoma size sheds doubt on this theory. GnRHa have been used successfully to achieve hypoestrogenism in various estrogen-dependent conditions, eg, endometriosis, precocious puberty, and uterine myomas. This approach offers great promise as a primary means of conservative therapy for myomas or as an adjunct to myomectomy. The effects of either progestational therapy or GnRHa treatment are transient, and within several cycles after discontinuing administration, myomas tend to return to their pre-therapy size. Adjunctive therapy with a 3 to 4 months course of GnRHa should reduce myoma size and render surgery easier, accompanied by less blood loss. Long-term treatment of young patients is neither practical nor desirable because of the likelihood of bone loss as a consequence of hypoestrogenism during prolonged therapy with GnRHa. For perimenopausal women, however, in whom reduction in myoma volume may stabilize when menopause occurs, short-term GnRHa therapy may eliminate the need for surgery. Hysterectomy: Removal of uterus has been the usual procedure of choice whenever surgery is indicated for uterine myomas and when childbearing considerations have been fulfilled. Indications for surgical management of uterine myomas: - Abnormal uterine bleeding not responding to conservative treatments.

- High level of suspicion of pelvic malignancy

- Growth after menopause

- Infertility when there is distortion of the endometrial cavity or tubal obstruction

- Recurrent pregnancy loss (with distortion of the endometrial cavity)

- Pain or pressure symptoms (that interfere with quality of life)

- Urinary tract symptoms (frequency and/or obstruction)

- Iron deficiency anemia secondary to chronic blood loss

In Webster's study, sexual function was not adversely affected by hysterectomy. The data in this study also provide evidence that the cervix and uterus are not required for coital orgasm. Two thirds of women in this study also experienced relief from urinary stress incontinence. Surgery to relieve bleeding, pain, pelvic pressure, and urinary tract symptoms may lead to improvement in sexual satisfaction and quality of life. Conservation of the cervix has been proposed for selected patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy because of its presumed significance in sexual function. However, in many studies it is seen there was no difference in the frequency of sexual activity and orgasm between women who underwent supracervical hysterectomy and those who had total hysterectomy.

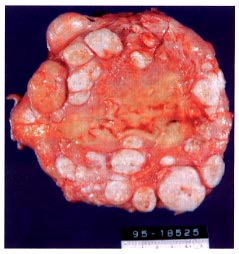

Cross section of a hysterectomy specimen obtained from a 40-year old woman who was a poor candidate for myomectomy because of extensive leiomyomatosis.

| Abdominal Myomectomy: Myomectomy is the preferred treatment whenever preservation of the uterus is desired. It is also the procedure of choice for a solitary pedunculated leiomyoma. Myomectomy should also be considered even if childbearing is not a factor for the women with symptomatic myomas who do not want a hysterectomy. Desire for uterine retention cannot be underestimated. Technology today even enables the uterus of a woman lacking ovaries to serve as a gestational vehicle by virtue of in vitro fertilization, endometrial preparation with exogenous hormone therapy, and embryo donation. Multiple myomectomy is frequently a more difficult and time-consuming procedure than hysterectomy. The number and location of myomas within the uterus, as well as the possibility of having had previous myomectomies and a history of recurrent myomas should be taken into consideration, before making the decision about myomectomy or hysterectomy. When extensive dissection of the myometrium has been necessary during myomectomy, cesarean delivery is usually advisable following establishment of pregnancy. When advising patients who desire pregnancy, the possibility of pelvic adhesions or the anatomic impairment of the interstitial portion of the oviduct as a result of dissection in this location after myomectomy should be discussed as an additional cause of postoperative infertility. Cervical myomas can be surgically removed with a vaginal approach in certain instances. The myomas can be removed through an already dilated cervix by advancing the bladder and making an anterior midline cervical incision. The myoma may be enucleated and the cervical incision repaired with interrupted sutures. Preoperative and perioperative antibiotic therapy is recommended in this approach because of the hazards of ascending infection from the vagina. Hysteroscopic Myomectomy: Hysteroscopy has been used for resection of submucousal myomas with very good results. Indications for Hysteroscopic myomectomy include abnormal bleeding, history of pregnancy loss, infertility, and pain. Contraindications include endometrial cancer, lower reproductive tract infection, inability to distend the uterine cavity, inability to circumnavigate the lesion, and extension of tumor deep into the myometrium. Long-term follow up studies have documented that approximately 20% of patients will require additional treatment within 5 to 10 years after initial resection. Mapping the myomas enables the hysteroscopist to plan the surgical approach. The European Society of Hysteroscopy classifies submucous myomas according to level of myometrial penetration.

Category T:O - all pedunculated submucous myomas.

Category T:I - Submucous myomas extending less than 50% into the myometrium.

Category T:II- Submucous myomas penetrating more than 50% into the myometrium.

Category T:O and T:I myomas can be performed hysteroscopically by a surgeon with modest previous experience. Category T:II myomas should be resected abdominally.

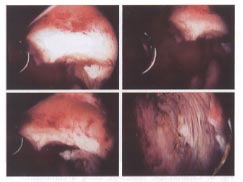

Different stages of hysteroscopic resection with a loop resectoscope of a submucosal leiomyoma in a woman with infertility.

| Laparoscopic Myomectomy: It can be performed when myomas are easily accessible, as in superficial subserous or pedunculated myomas. These myomas can be morcellated and removed through the laparoscopic cannula or placed in the cul-de-sac and removed via a colpotomy incision. The procedure of myolysis is viewed as a conservative alternative to myomectomy in women wishing to preserve fertility. The procedure can be carried out with the energy of a neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd:YAG) laser via denaturation of protein and destruction of vascularity. Bipolar coagulation and cryomyolysis have also been described, but sufficient follow up has not been available to enable adequate evaluation of safety and the impact on future fertility. Uterine rupture during pregnancy following laparoscopic resection of leiomyomata has been reported and has been attributed to inadequate reconstruction of the myometrium. Laparoscopic assisted myomectomy involves laparoscopic dissection of the myomas from the uterine wall and their extraction through mini-laparotomy incision, thus sparing a large abdominal incision.

Laparoscopic resection, using a combination of bipolar coagulation and endo-shears, of multiple subserous myomas in an infertility patient.

|

Morcellation and extraction of the resected myomas following laparoscopic myomectomy with a grasping forceps and an electrical morcellator.

| The patient contemplating myomectomy should be aware of the risks involved in "conservative" surgery, as well as those associated with hysterectomy for myomas. For those who wish to conceive, a delay of 4 to 6 months before attempting pregnancy is recommended after the surgical procedure, because the myometrium is significantly disrupted during myomectomy. For infertility patients we recommend hysterosalpingogram (HSG) 4 months after the procedure to evaluate the anatomy of the uterine cavity and the fallopian tubes. Uterine Artery Embolization: This treatment for myomas was first described in 1995. The principle is, by limiting blood supply to the myomas (infarction), their volume may be reduced. The Embolization material, usually polyvinyl alcohol particles, is passed through a fluoroscopically guided transarterial catheter inserted in the common femoral artery to selectively occlude arteries supplying the myomas. The procedure is performed under conscious sedation by an interventional radiologist. Because of the shortened hospital stay, this minimally invasive procedure has become an attractive new alternative to abdominal surgery. It has been recommended for patients with larger myomatous uteri who are symptomatic, women who do not want extirpative therapy, and individuals who may be poor candidates for major surgery. Most patients require over night hospitalization for pain control. Because of newness of this approach, several questions remain to be answered, like its long-term effect on infertility, and overall safety compared with conventional surgical treatment. Side effects and complications: Pain may persist and last for more than 2 weeks after the procedure. Post-embolization fever, severe post-embolization syndrome, pyometra, failure of satisfactory regression of myomas, sepsis, hysterectomy, and even deaths has been reported following uterine artery embolization. Ovarian failure has also been reported in 1-2% of patients after the embolization procedure. Conclusion:A thorough understanding of the pathogenesis of uterine myomas, clinical presentation, and the available diagnostic tools are the keys to selecting which course to follow in treating any given patient with myomas. The experience and skill of any individual surgeon is paramount in selecting the form of treatment for myomas. The surgery for myomas is not always necessary and should be performed only for appropriate indications, such as uncontrollable pain or bleeding, progressive and significant growth, and poor reproductive performance once other potential causes have been eliminated or treated. Suggested Reading: Edward E. Wallach and Nikos F. Vlahos. Uterine Myomas: An Overview of Development, Clinical Features, and Management. Obstetrics and Gynecology; Vol.104, NO 2, August 2004: 393-406. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists publication; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins publisher. Acknowledgement: We are grateful to Dr. Edward E. Wallach for sharing his priceless work and research with us. His work in reproductive health has helped millions of women to live a better life. We are looking forward to work with him for many more years

©

Women's Health and Education Center (WHEC)

|