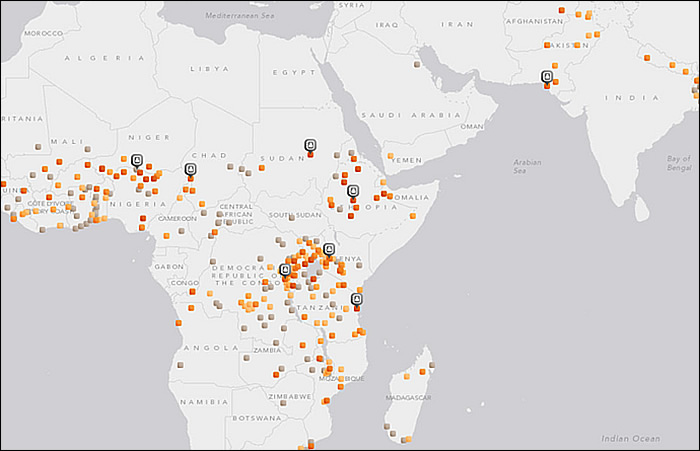

Global Efforts to End Obstetric Fistula (Part 1)WHEC Practice Bulletin and Clinical Management Guidelines for healthcare providers. Educational grant provided by Women's Health and Education Center (WHEC) Obstetric fistula is a devastating childbirth injury that leaves women incontinent, often stigmatized, and isolated from their communities. It is a stark outcome of socioeconomic and gender inequalities, human rights denial and poor access to reproductive health services, including maternal and newborn care, and an indication of high levels of maternal death and disability. The report outlines efforts made at the international, regional and national levels, and by the United Nations system, to end obstetric fistula. It offers recommendations to intensify these efforts, within a human rights-based approach, to end obstetric fistula as a key step towards achieving Millennium Development Goal 5, by improving maternal health, strengthening health systems, reducing health inequities, and increasing the levels and predictability of funding. The 2005 World Health Report identified the need for partnerships to bridge the gap between knowledge and action in improving maternal and newborn health. Stronger partnerships can bring the capacity of non-government organizations (NGOs) to provide quality obstetric services and to achieve United Nations Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5, which aim to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality and the under-5 mortality rate by two thirds. It also aims to ensure universal access to reproductive health care. NGOs have been found effective in providing delivery care in developing countries and should be recognized by stakeholders in their efforts to assist nations achieve international goals. The purpose of this document to review the global efforts to end obstetric fistula and recommend effective delivery care in developing countries and awareness of the magnitude of this catastrophic childbirth injuries. Almost all obstetric fistulae occur in resource-poor areas, as a paucity of resources is the root cause. Where there are no suitable facilities for deliveries and obstetric emergencies, obstruction of labor often results in fetal death and obstetric fistula. Treatment in this setting usually focuses on meeting patients’ immediate needs rather than conducting research and refining techniques and long-term management of the patients. Unified, standardized evidence-base for informing clinical practice is lacking. This review addresses magnitude of the problem and efforts at international, national and regional levels. Introduction:Sexual and reproductive health problems remain the leading cause of ill health and death for women of childbearing age worldwide. Impoverished women, particularly those in developing countries, suffer disproportionately from limitations on their right of access to health care, from unintended pregnancies, maternal death and disability, sexually transmitted infections including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cervical cancer, sexual and gender-based violence, and other problems related to their reproductive system. Educating and empowering women and girls are crucial for their well-being, and fundamental for preventing obstetric fistula and improving maternal health. Educated women and girls better understand how to exercise their reproductive health choices, the benefits of seeking appropriate care during pregnancy and delivery, why to delay marriage until adulthood and how to ensure the well-being of their children and families. Currently, there are as many as 3.5 million women in Africa and Asia, with up to 130,000 new cases of obstetric fistulae occurring each year (1). In the vast majority of cases, obstetric fistulae are caused by ischemic necrosis of the tissues of the vesicovaginal septum that are trapped between mother’s bony pelvis and the presenting fetal part (usually the head). In parts of the world without prompt access to emergency obstetric care, women may remain in obstructed labor for 3 or 4 days (or longer) without delivery (2). After delivery (usually of a stillborn fetus), the necrotic tissue sloughs away to reveal the fistula. Background:Obstetric fistula is a severe maternal morbidity which can affect any woman or girl who suffers from prolonged or obstructed labor without timely access to an emergency Caesarean section. It is one of the most devastating consequences of neglected childbirth and a stark example of health inequity in the world. Although obstetric fistula has been eliminated in industrialized countries, it continues to afflict the most impoverished women and girls in the developing world, mainly those in rural and remote areas. Eliminating obstetric fistula as a global health problem necessitates scaling up country capacity to provide access to comprehensive emergency obstetric care, treat fistula cases, and address underlying medical, socioeconomic, cultural and human rights determinants. To end obstetric fistula, countries must ensure universal access to reproductive health services; eliminate gender-based social and economic inequities; prevent child marriage and early childbearing; promote education and broader human rights, especially for girls; and foster community participation in finding solutions, including through the active involvement of men The medical and social consequences of obstetric fistula can be life-shattering for women, their children and families. In almost 90 per cent of fistula cases, the baby is stillborn or dies within the first week of life (3). If a woman survives prolonged or obstructed labor, she may be left with a severe, disabling injury in her birth canal. A woman with fistula is not only left incontinent but may also experience neurological disorders, orthopedic injury, bladder infections, painful sores, kidney failure or infertility. The odor from constant leakage combined with misperceptions about its cause often results in stigma and ostracism by communities. Many women with fistula are abandoned by their husbands and families and are excluded from daily family and community life. They may find it difficult to secure income or support, thereby deepening their poverty. Their isolation may affect their mental health, resulting in depression, low self-esteem and even suicide. While precise figures are not available, it is generally accepted by the United Nations that from 2 million to 3.5 million women and girls live with obstetric fistula (4). Determining the prevalence and incidence, however, is extremely difficult as fistula usually afflicts the most marginalized – poor, young, often illiterate women and girls living in rural areas – and usually requires clinical screening to diagnose. Obstetric fistula can be prevented. Tackling the root causes of maternal mortality and morbidity is essential, including poverty, gender inequality, barriers to education – especially for girls – child marriage and adolescent pregnancy. It requires functioning, accessible health systems. It needs adequately trained professionals, reliable access to essential medicines and equipment, and equitable access to high-quality reproductive health services. Broader economic and socio-cultural changes are required to prevent obstetric fistula. Poverty and gender inequality impede women’s opportunities, including access to health services. Culture also influences the status of their sexual and reproductive health, the age of marriage, the spacing and number of children. Traditions favoring unassisted home delivery, including the use of unskilled traditional birth attendants and harmful practices such as female genital mutilation and child marriage further inhibit maternal health. Health-care costs can be prohibitive for poor families, especially when complications occur. These factors contribute to the three delays that impede women’s access to health care: delay in seeking care; delay in arriving at a health-care facility; and delay in receiving adequate care once at the facility. Adolescent girls are particularly at risk of maternal deaths and morbidities, including obstetric fistula. Although adolescent births represent approximately 11 per cent of births worldwide, they account for 23 per cent of the burden of disease among women of all ages (5). Sixteen million adolescent girls give birth each year; almost 95 per cent of those births occur in developing countries.4 Complications of pregnancy and childbirth are the leading cause of death among girls 15 to 19 years old in low- and middle-income countries. Evidence suggests that delaying pregnancy until after adolescence may reduce the risk of obstructed labor and obstetric fistula. Malnutrition among girls may stunt growth. Pregnancies that occur early, before the pelvis is fully developed, can increase the risk of obstructed labor. Child marriage affects one in three girls in the developing world, predominantly the poorest, least educated girls living in rural areas. Although age at marriage is generally rising, millions of girls in developing countries are expected to marry before age 18 (6). Impoverished, marginalized girls are more likely to marry as children and give birth during adolescence than girls with greater education and economic opportunities. Child marriage is a key driver of early pregnancy and childbearing before adolescent girls are physically or emotionally ready, which heightens their risk of maternal death and morbidities, including fistula. Married adolescent girls often have difficulty accessing reproductive health services for reasons including social isolation and lack of awareness of their reproductive rights. All adolescent girls and boys, both in and out of school, married and unmarried, need access to comprehensive sexuality and human rights education, life skills education, and health services including sexual and reproductive health, to protect their well-being. There is consensus in the global health community on the three most cost-effective interventions to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity, including obstetric fistula. They are: universal access to family planning; a trained health professional with midwifery skills at every childbirth; and timely access to high quality emergency obstetric and newborn care. Prevention is a core component of effective strategies to end fistula, of which abandonment of harmful practices, such as child marriage, is crucial. The same interventions that reduce maternal mortality reduce fistula. Several low-income countries, including Bolivia (Plurinational State of), Eritrea, Nepal, Rwanda and Yemen, have made progress in reducing maternal mortality over the past 10 years. In Afghanistan, antenatal care and skilled delivery coverage more than tripled from 2003 to 2010, thereby significantly reducing the maternal mortality ratio from an estimated 1,400 per 100,000 live births in 2008 to 460 in 2010.6 The Islamic Republic of Iran, with a maternal mortality ratio of 30,7 is one of 10 middle-income countries that have reached the Millennium Development Goal 5 target of reducing the maternal mortality ratio by three quarters by strengthening maternal health systems (7). In Egypt, the Ministry of Health made reducing the maternal mortality ratio a national priority and concentrated on regions with the highest incidence of maternal death.9 The maternal mortality ratio in Egypt declined from 230 in 1990 to 66 in 2010.8 The Russian Federation has successfully cut its maternal mortality ratio by more than half over the past two decades, from 74 to 34. Algeria and Chile reduced their maternal mortality ratios by over 50 per cent from 1990 to 2010. The Arab States have made commendable progress, reducing the maternal mortality ratio by 65 per cent or more in Morocco, Oman and Yemen; around 50 per cent or more in Qatar, Tunisia and the United Arab Emirates; and over 40 per cent in Jordan, Libya and Saudi Arabia. Qatar and the United Arab Emirates have achieved maternal mortality ratios below those of many other countries, including the United States of America (8). Most cases of obstetric fistula can be treated through reconstructive surgery. Women can then be reintegrated into their communities with appropriate psychosocial care. However, research suggests that there is a huge gap between the need for fistula treatment and available services. Currently, few health-care facilities are able to provide high-quality fistula surgery, owing to the limited number of health-care professionals with the necessary skills. Facilities that do exist may not function at maximum capacity for lack of trained health professionals, equipment and life-saving medical supplies. When services are available, many women are not aware of, or cannot afford or reach the services, owing to such barriers as transportation costs. A global fistula mapping exercise conducted in 2010 by Direct Relief International, the Fistula Foundation and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) found that fistula treatment reaches only a fraction of fistula patients annually – approximately 14,000 cases compared to the estimated 50,000 to 100,000 new cases each year – highlighting the need for intensifying resources to bridge this large gap (9). UNFPA launched the global Campaign to End Fistula in 2003, with partners, with the goal of making fistula as rare in developing countries as in the industrialized world. The Campaign focuses on three key strategies: prevention, treatment and social reintegration. It is active in over 50 countries in Africa, Asia, the Arab States and Latin America and brings together more than 75 partner agencies at the global level and many others at the national and community levels. Since the Campaign began, UNFPA has directly supported over 27,000 women and girls to allow them to receive surgical treatment for fistula, and partners such as Engender Health supported thousands more. As the tenth anniversary of the Campaign to End Fistula approaches, numerous challenges have still to be met. Many women and girls continue to suffer isolation for want of treatment. According to an independent evaluation in 2010, the Campaign has enhanced the visibility and knowledge of obstetric fistula worldwide, yet it is critically under-resourced and requires far more financial and human resources to achieve its goal of eliminating fistula. UNFPA serves as the secretariat for the International Obstetric Fistula Working Group – the main decision-making body of the Campaign to End Fistula. The Working Group promotes effective, collaborative partnerships and generates consensus and evidence regarding effective strategies for preventing and treating fistula and reintegrating women living with fistula into society. What is the Global Fistula Map?

Why is it Relevant?

Female Genital Cutting and Obstetric Fistulae:Female genital cutting (also commonly referred to as either “female circumcision” or “female genital mutilation”) refers to “all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons (10). Over the past 20 years, female genital cutting has undergone increasingly critical scrutiny because of the adverse health consequences of such practices (11). Only a small number of studies have looked at potential linkages between genital cutting and women’s reproductive health. Recently study (12) evaluated presumed association between female genital cutting and obstetric fistulae formation during obstructed labor. This study concluded that adverse outcomes increased according to the severity of genital cutting, with significant increases in the risk for cesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, episiotomy, extended maternal hospital stay, and the need for infant resuscitation at delivery. Female genital cutting appeared to lead to one or two additional perinatal deaths per 100 deliveries. This study did not find any clear differences in the presentation, site, size, or degree of scarring in obstetric fistulae occurring in women who have undergone type I or type II genital cutting procedures compared with women with obstetric fistulae who have not been cut in this way. Surgical outcomes do not differ according to whether or not the woman has previously undergone female genital cutting, and physical examination gives the clear impression that the amount of scarring left by type I and type II cutting procedures would not cause a prolonged labor. Both of these observations suggest that type I and type II genital cutting does not contribute to obstetric fistula formation during obstructed labor (12). Furthermore, statistical modeling using data from demographic and health surveys carried out in Malawi, Rwanda, Uganda, and Ethiopia have not found evidence that genital cutting contributes to fistula formation from obstructed labor (13). Type I and type II female genital cutting may not have clear association of obstetrical fistula but obstetric fistulae are prevalent in cultural areas where genital cutting practices are also common. Rather than being a cause obstructed labor, female genital cutting is a marker for the presence of other important risk factors that combine to promote fistulae (1). Fistulae are found where the socioeconomic status of women is low, where early marriage is common and pregnancy occurs before pelvic growth is complete, where women’s personal autonomy is highly restricted, where contraceptive choice is limited or non-existent and fertility is high, where women are largely uneducated and have little political power, and where transportation is difficult and the medical infrastructure is inadequately developed so that timely access to emergency obstetric services is poor and those services are often marginal quality. Together, these factors combine to produce high levels of maternal mortality and obstetric morbidity, of which the obstetric fistula is a common tragic component. Initiatives at the International, Regional and National Levels:Major International Initiatives For more than two decades, the United Nations and the international community have campaigned to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity. Global commitments were first made in 1987 at the International Safe Motherhood Conference in Nairobi. The Programme of Action adopted at the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo in 1994 recognized maternal health as a key component of sexual and reproductive health. In 1995, at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, Governments, adopting the Platform for Action, recognized entrenched patterns of social and cultural discrimination as major contributors to sexual and reproductive ill-health, including maternal death and disability. Member States have upheld the right of women and girls to the highest attainable standard of mental and physical health, including sexual and reproductive health, through the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. In 2000, world leaders reaffirmed their commitment to improve maternal health, adopting Millennium Development Goal 5 to reduce the maternal mortality ratio by three quarters by 2015 (14). The target of universal access to reproductive health under Goal 5 ensures full coverage of all factors necessary for improving maternal health. Goals 3, 4 and 6 are also essential for women’s health, well-being and survival. Achieving Goal 1, eradicating extreme poverty, will significantly contribute towards eliminating maternal mortality and fistula. In 2010, data showed for the first time good progress towards reaching Millennium Development Goal 5; however, an estimated 96 countries will not reach the target until at least 20 years after 2015 if the current pace continues (15). The General Assembly first recognized the problem of obstetric fistula in 2005 in its resolution 60/141 on the girl child. It identified early childbearing and limited access to sexual and reproductive health as key factors in the persistence of obstetric fistula and maternal mortality. In 2007, the General Assembly for the first time acknowledged obstetric fistula as a major women’s health issue by adopting resolution 62/138 on supporting efforts to eliminate obstetric fistula. In 2010 the Assembly adopted resolution 65/188, sponsored by a record-breaking 172 States, calling for renewed focus and intensified efforts for eliminating obstetric fistula. States reaffirmed their obligation to promote and protect the rights of all women and girls and to contribute to efforts to end fistula, including to the global Campaign to End Fistula. Launched in 2008 by UNFPA and the International Confederation of Midwives, the Midwifery Programme helps countries to strengthen their midwifery programmes and policies. The programme aims to improve skilled attendance at all births in low-resource countries. It supports national midwifery training and education; developing strong regulatory mechanisms promoting quality midwifery services; strengthening and establishing midwifery associations; and advocating with Governments and stakeholders to encourage investment in midwifery services. The programme is active in over 30 countries in Africa, Asia, the Arab States and Latin America. More than 2,000 midwives have been trained and 150 midwifery schools provided with books, clinical training, equipment and supplies. The High-level Plenary Meeting of the General Assembly on the Millennium Development Goals, in 2010, revealed that Millennium Development Goal 5 had the least financial support and lagged behind all other Goals. Of the 68 countries that account for most maternal and child deaths, only 16 per cent were on track to reach Goals 4 and 5 by 2015. In response, a Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health was launched with the objective of saving the lives of more than 16 million women and children by 2015. The Global Strategy, or Every Woman Every Child, presents a road map to enhance health financing, strengthen policy and improve services on the ground for vulnerable women and children. In 2011, the Human Rights Council adopted a landmark resolution on preventable maternal mortality and morbidity and human rights (resolution 18/2), applying a human rights-based approach to policies and programmes to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity. The Commission on the Status of Women, in March 2012, adopted the biannual resolution 56/3, on eliminating maternal mortality and morbidity through the empowerment of women, calling for the elimination of preventable maternal mortality and morbidity and strengthening comprehensive health services for women and girls, including access to sexual and reproductive health. Reaffirming the need to promote gender equality and the empowerment of girls and young women in all aspects of youth development, the Commission on Population and Development adopted resolution 2012/1. In response to the substantial unmet need for family planning services worldwide and recognizing family planning as a key component of reproductive health, including fistula prevention, in July 2012, at the London Summit on Family Planning, donors committed over $4 billion for family planning. This initiative aims to give 120 million more women in developing countries access to voluntary family planning by 2020. Major Regional Initiatives Concerned about insufficient progress on Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5, the African Union, with United Nations support, has intensified efforts to improve sexual and reproductive health throughout Africa. In 2003, the African Regional Reproductive Health Task Force called for the development of national road maps to accelerate the reduction of maternal and newborn mortality. The plan, endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO), UNFPA, United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), the World Bank and others, aims to help Governments to plan and mobilize support for skilled attendance during pregnancy, childbirth and the postnatal period, and to strengthen national health systems. To date, more than 42 African countries have developed road maps, and 9 have conducted midterm reviews and created implementation plans. In 2006, African Union Heads of State endorsed the Continental Policy Framework on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights. The Framework, or the Maputo Plan of Action, addresses reproductive health challenges in Africa and includes a substantial component on obstetric fistula, calling for health sector strengthening and increased resource allocations for health. While some progress has been made in implementing the Maputo Plan of Action, resources remain very limited, few countries having a budget line for sexual and reproductive health.14 Leaders have extended the Maputo Plan of Action from 2010 to 2015. The Campaign on Accelerated Reduction of Maternal Mortality in Africa promotes intensified implementation of the Maputo Plan of Action in Africa. UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO, bilateral donors and civil society organizations support the Campaign at the national and regional levels. The Campaign initiates policy dialogue, advocacy and community mobilization to secure political commitment, increase resources and effect societal change in support of maternal health at the country level. At the regional conference on obstetric fistula and maternal health in Côte d’Ivoire in 2008, an African network of civil society organizations was launched. The network leverages technical and financial resources and promotes South-South cooperation to address obstetric fistula and promote maternal health. In 2009, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) adopted the Joint Declaration on the Attainment of the Millennium Development Goals in ASEAN, which includes the development and implementation of a road map for achieving the Millennium Development Goals. In 2011, the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights organized a conference in the Philippines, which identified region-specific good practices for reducing maternal mortality and morbidity. It called for renewed efforts to improve maternal health with increased budget allocations, and legislation to promote women’s right to reproductive health, including safe pregnancy and affordable family planning services. Promoting the theme, “Neglected no more – dignity restored”, UNFPA supported a regional conference on fistula in Pakistan in 2011 bringing together 1,200 participants from 14 countries, including 10 international fistula surgeons. The event was an important milestone in highlighting obstetric fistula in Pakistan and secured the strong commitment of the Pakistan Ministry of Health to establish a national task force for fistula. The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) initiated a regional project to reduce child and maternal mortality through improving the skills of health professionals, providing comprehensive mother-and-child primary health care and improving infrastructure and equipment at the district and sub-district levels. The project is financed by the newly established SAARC Development Fund. In the Latin American and Caribbean region, a Regional Inter-Agency Task South-South collaboration is a key strategy of the Campaign to End Fistula. Since 2010, UNFPA and its partners have supported the sharing of knowledge, skills and resources among many countries. The Niger welcomed a team of doctors and surgeons from Haiti; in Ethiopia the Hamlin Fistula Hospital treated complex fistula cases from the Sudan; and South Africa treated fistula cases from Swaziland. Bangladesh provided training on fistula surgery, management and counseling to health professionals in Nepal and performed complicated fistula surgeries on women in Timor-Leste. Doctors from Pakistan travelled to Kenya for training on new techniques in post-surgical incontinence. In Benin, UNFPA, in partnership with civil society and the USAID Integrated Family Health project, supported the training of fistula surgeons from Chad and Mauritania on the latest techniques in fistula repair. A Senegalese fistula surgeon performed fistula surgery in Chad, Gabon and Rwanda. Lesotho sent fistula patients to South Africa for treatment. The ministries of health in South Sudan and Uganda signed an agreement enabling South Sudanese students to commence midwifery studies in Uganda. Major National Initiatives Improving reproductive health must be a country-owned and country-driven process. To accelerate progress towards reducing maternal mortality and ending fistula, countries urgently need to allocate a greater proportion of their national budgets to health, especially reproductive health. Countries also require intensified, additional international technical and financial support. Progress has been made on integrating obstetric fistula into countries’ national health policies and plans, including in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Madagascar, Mozambique, Sierra Leone, the Sudan and Uganda. In Afghanistan, the revised reproductive health policy and strategy focused on male involvement, emergency obstetric care, fistula and gender-based violence. In May 2012, the Government of Chad organized a conference to strengthen implementation of the national strategy for the fight against fistula, and to revitalize the National Task Force for Fistula. To facilitate coordinated planning and interaction between partners working on all aspects of obstetric fistula, several countries have created a National Task Force for Fistula. These task forces are typically led by ministries of health, and comprise civil society organizations, medical providers and United Nations agencies. To date, 14 countries have developed national task forces for fistula, including Afghanistan, the Central African Republic, Mali and South Sudan. The Uganda task force serves as a role model, meeting regularly to enhance dialogue and coordination of fistula activities. Countries around the world are reinforcing policies and strategies to better protect women and girls, and address multiple forms of gender-based violence, including human trafficking, sexual violence and exploitation, female genital mutilation/cutting and child marriage. The Government of the Niger has made gender equity, access to reproductive health, and zero tolerance of violence against women and girls constitutional rights. Most countries with high rates of child marriage, including Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, the Central African Republic, Eritrea, Ethiopia, India, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Nepal, Nicaragua and Uganda, have enacted legislation setting the minimum age of marriage at 18. Others are eliminating differences in the legal age between boys and girls. Enforcing such national laws is often challenging in rural and remote areas, however. In 2011, UNFPA, jointly with United States Representative Carolyn Maloney and Campaign to End Fistula partners, organized a Congressional briefing in Nongovernment Organizations (NGOs) and Faith-Based Organizations The 2005 World Health Report identified the need for partnership to bridge the gap between knowledge and action in improving maternal and newborn health. NGOs and faith-based organizations can fill gaps in health services, which they already provide in many low-income countries. Stronger partnerships can bring the capacity of NGOs and faith-based organizations to achieving United Nations Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5, which aim to reduce maternal and child morbidity and mortality. The WHO has estimated that 30-70% of health infrastructure across Africa is owned or run by NGOs / faith-based organizations (16). Higher rates of poor outcomes in government institutions could be due to lower rates of antenatal care, less access to peripartum services, or quality-of-care issues. The higher rates of admission of women to the intensive care and transfusions in government institutions may reflect differences in hospital policy or greater access to lifesaving care, rather than merely higher complication rates. The critical role played by NGOS and faith-based organizations should be recognized by governments, stakeholders, donors, and international agencies. Greater recognition and integration of NGOs and faith-based organizations into strategies to improve maternal and neonatal health is essential, given both the volume and quality of care they already contribute. Good outcomes following delivery in NGOs / faith-based organizations may be the result of better infrastructure, obstetric services, and specialist attendance at birth (16). Future research should investigate institutional and patient characteristics associated with improved maternal and perinatal outcomes in NGOs / faith-based organizations and government-run institutions in developing countries. Conclusions and Recommendations:Obstetric fistula is an outcome of socioeconomic and gender inequalities and the failure of health systems to provide accessible, equitable, high-quality maternal health care, including family planning, skilled attendance during childbirth and emergency obstetric care in case of complications. Over the past two years, considerable progress has been made in focusing attention on maternal deaths and disabilities, including obstetric fistula. Despite these positive developments, many serious challenges remain. It is a grave injustice that around the world, in the twenty-first century, the poorest, most vulnerable women and girls suffer needlessly from a devastating condition that has been virtually eliminated in the industrialized world. Significantly intensified political commitment and financial mobilization are urgently needed to accelerate progress towards eliminating this global scourge and closing the gap in the unmet need for fistula treatment. Special attention should be paid and support intensified to countries with the highest maternal mortality and morbidity rates, especially those struggling to make sufficient progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5, for example, Burundi, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Congo, Guinea- Bissau, Lesotho, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan and Zimbabwe. There is global consensus on the key interventions necessary to reduce maternal deaths and disabilities. Countries are increasingly investing in and promoting prevention, treatment and reintegration services for women living with obstetric fistula as part of holistic efforts to achieve Millennium Development Goal 5. There is, however, an urgent need to scale up the three well-known, cost-effective interventions, emphasizing the crucial role of midwives to reduce the high number of avoidable maternal deaths and disabilities. Better understanding of the social and economic burden resulting from poor reproductive and maternal health has led to multi-sector approaches to address linkages between poverty, inequities, gender disparities, discrimination, poor education and health. Efforts to improve women’s health should systematically include educating women and girls, economic empowerment, including access to microcredit and microfinance, and legal reforms and social initiatives to increase the age of marriage and delay early pregnancy. Eradication of female genital cutting is desirable from the standpoints of both women’s health and human rights the elimination of these traditional genital operations will not eliminate obstetric fistulae as a complication of child birth. Accomplishing this will require the presence of a trained attendant during every labor and timely, universal access to competent emergency obstetric services worldwide. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and faith-based organizations in Africa are comparable to government-run institutions in terms of infrastructure and capacity to deliver obstetric care. Higher rates of obstetrician attendance and cesarean / instrumental delivery occurred at these institutions, potentially indicating better access to lifesaving intrapartum care. Greater recognition and integration of NGOs and faith-based organizations into strategies to improve maternal and neonatal health are essential for reaching international targets. Suggested Reading:

Funding:Provided by Global Initiatives of Women’s Health and Education Center (WHEC) and its partners to improve maternal and child health worldwide. References:

|