Pelvic Organ Prolapse: An Overview

Dr.Alka Shaunik and Dr. Lily A. Arya

Division of Uro-gynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia 19104 (USA)

Phone: 215 349 5049

Fax: 215 662 7929

Email: larya@mail.obgyn.upenn.edu

Pelvic organ prolapse is a very common gynecological condition - it is estimated that 50% of women who have had even one childbirth, lose pelvic floor strength and about 10 to 38% of these women, between 15 to 60 years of age suffer from full blown prolapse. The incidence increases with advancing age. Unfortunately, only 1 in 5 patients are able to access medical care for their symptoms. Every year nearly 2.04 women per thousand year's risk are hospitalized for prolapse and almost 338,000 undergo surgical interventions for the disorder. This high incidence places a severe social and economic burden on the society.

The social stigma of genital tract sickness leads to under-reporting - only 20% of the affected women seek medical assistance. The odor and leakage are associated with disability, embarrassment, psycho-social withdrawal and further deterioration in health due to reduced access to health care systems.

A large number of cases of pelvic organ prolapse go undetected even in the physician's office, owing to the great variety of clinical presentations. The existence of different varieties of prolapses individually or concomitantly in the same patient makes the diagnosis even more complex.

Loss of support of anterior, posterior, and apical vaginal walls results in cystocele, rectocele, enterocele, and vaginal cuff prolapse, respectively. Utero-vaginal prolapse occurs secondary to damage of the cardinal-uterosacral ligament complex and endopelvic fascia that normally support the uterus and upper vagina over the pelvic diaphragm. Connective tissue defects have been found in women with uterine prolapse and stress incontinence. The abnormal connective tissue may be associated with pelvic organ prolapse and stress incontinence.

Classification of the Severity of Pelvic Organ Prolapse:

Cystocele

Cystocele or Anterior vaginal prolapse is defined as pathologic descent of the anterior vaginal wall and overlying bladder base. According to the International Continence Society (ICS) standardized terminology for prolapse grading, the term Anterior Vaginal Prolapse is preferred over cystocele.

First Degree - the anterior vaginal wall, from the urethral meatus to the anterior fornix, descends halfway to the hymen.

Second Degree - the anterior vaginal wall and underlying bladder extend to the hymen.

Third Degree - the anterior vaginal wall and underlying urethra and bladder are outside the hymen. This cystocele is often part

of the third-degree uterine or post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse.

Uterine or Vaginal Vault Prolapse

First Degree - the cervix or vaginal apex descends halfway to the hymen.

Second Degree - the cervix or vaginal apex extends to the hymen or over the perineal body.

Third Degree - the cervix and corpus uteri extend beyond the hymen or the vaginal vault is everted and protrudes beyond the

hymen.

Rectocele

Rectocele may be defined as herniation or bulging of the posterior vaginal wall, with the anterior wall of the rectum in direct apposition to the vaginal epithelium. Rectocele is fundamentally a defect of the recto-vaginal septum, not the rectum. The term Posterior Vaginal Prolapse is preferred over rectocele.

First Degree - the saccular protrusion of the recto-vaginal wall descends halfway to the hymen.

Second Degree - the sacculation descends to the hymen.

Third Degree - the sacculation protrudes or extends beyond the hymen.

Enterocele:

Enterocele is a hernia in which peritoneum is in intact with vaginal mucosa. The normal intervening endopelvic fascia is absent, and small bowel fills the hernia sac.

The presence and depth of the Enterocele sac, relative to the hymen, should be described anatomically, with the patient in the supine and standing positions during Valsalva maneuver.

International Continence Society Stages of Pelvic Organ Prolapse Determined by Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System Measurements:

Stage 0 No prolapse; anterior and posterior points are all -3 and C (cervix) or D (posterior fornix) is between - TVL (total Vaginal length) and - (TVL - 2) cm.

Stage I The criteria for stage 0 are not met, and the most distal prolapse is >1 cm above the level of the hymen (< -1 cm).

Stage II The most distal prolapse is between 1 cm above and 1 cm below the hymeneal ring (at least one point is - 1, 0,

or +1).

Stage III The most distal prolapse is between >1 cm below the hymeneal ring, but no further than 2 cm less than TVL.

Stage IV Represents complete vault eversion; the most distal prolapse protrudes to at least (TVL - 2 ) cm.

The experience of childbirth is the only logical explanation for the presence of pelvic organ prolapse exclusively in women. Research suggests that pelvic floor dysfunction, which is the precursor of prolapse, is most likely caused by single or repeated childbirths. The patho-physiologic mechanisms by which injuries at childbirth cause an increased incidence of prolapse are yet to be studied in detail. But, most studies observe that the poor countries with poor obstetric care, ill trained local birth attendant and primitive obstetrical practices show a higher incidence of frank pelvic organ prolapse. In western countries, with better quality of obstetrical care only the milder form of the disease - pelvic organ dysfunction is seen. Other known factors associated with higher incidence of prolapse are: increasing number of pregnancies and childbirths, increasing number of vaginal births, delivery of large size baby, straining at the time of labor before the full dilation of the cervix, history of malnutrition, postmenopausal status, and hypertension and generalized neuromuscular weakness. The resulting prolapse may develop immediately after the occurrence of the incident or may take years to become clinically evident.

Symptoms associated with varying Degrees of Prolapse:

Mild prolapse usually presents as mild discomfort and a feeling of dragging down in the pelvic region.

Moderate prolapse may lead to a feeling of pressure in the vagina, discomfort/ pain while standing or pain during sexual intercourse.

Severe prolapse is the dropping of the pelvic organs so far below that they become visible from the vagina. Severe prolapse may cause symptoms of urinary incontinence, voiding dysfunction, symptomatic dropping of the uterus, post surgical vault prolapse, fecal incontinence, sexual dysfunction and difficulty in passing stool.

Treatment Modalities:

Patients with mild symptoms can be successfully managed with medications, physiotherapy, behavioral therapy, pessaries, and advised use of vaginal pads and odor neutralizers, before the surgical intervention. Various effective surgical procedures are available to preserve the form and function of the genital tract depending on the age, fertility and sexual activity requirements of each woman. Vaginal route for prolapse repair is preferred because: ability to repair anterior, apical and posterior support defects, ability to treat stress urinary incontinence, avoidance of incision and wound complications, decreased costs and operative time, and quicker return to activities of daily living. Disadvantage may be possible decrease in vaginal length.

Sexual Dysfunction - It is an important quality-of-life consideration for the patient undergoing pelvic reconstructive surgery. Some studies have shown after bilateral uterosacral ligament suspension and site-specific vaginal reconstruction, total vaginal length decreased by 0.75 cm on average, with 88% having a vaginal length of 7 cm or greater. The same study described 29 patients with vaginal correction of stage III or IV prolapse, and found their sexual satisfaction remained high and symptoms of dysparunia were unchanged from base-line at 6 months after surgery. From a sexual function perspective, abdominal vaginal suspension should be performed on patients who have a fore-shortened vagina at baseline and who desire to maintain vaginal sexual activity. Following the surgery there may be mild side effects like pain or dyspareunia; serious side effects like vault prolapse or prolapse of a another genito-urinary organ after operative intervention may occur in rare circumstances.

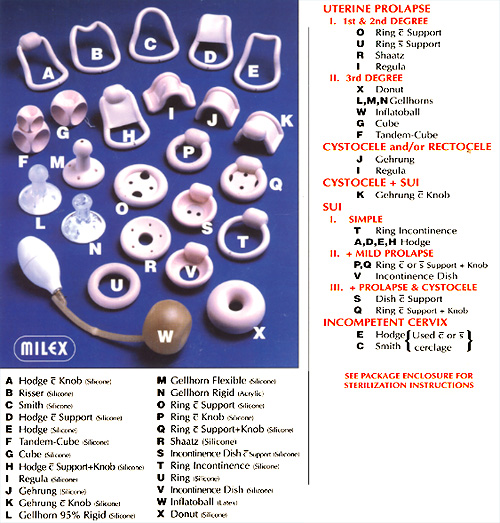

Mechanical Devices - With the advent of modern surgical techniques, pessaries were considered a relic of the past and for a period of time were rarely offered or used. Recently, there has been a resurgence of interest in this therapeutic modality. Physicians are becoming more conscious of the long-term risks and failure rates of surgical procedures, and patients are becoming more interested in considering all options for their problem. Some patients choose to wear a pessary as the final therapy for their pelvic floor dysfunction, whereas others use a pessary to temporize before considering surgery and many more wear such a device daily only when undertaking an activity that results in urine loss, such as exercise. We believe that offering appropriate candidates the choice of expectant management, a pessary other device, or surgery constitutes good informed consent. A pessary also can be a useful diagnostic tool for the clinicians.

Today, many pessaries and vaginal devices are available to treat incontinence and or prolapse. Some are easier for a woman to manage herself than others. Our approach is to begin a fitting session with one of the more inexpensive, user-friendly devices before proceeding to pessaries that are more expensive or more difficult for the patient to manage. In our experience, adverse outcomes from wearing a pessary, such a vaginal abrasions or ulcerations, are rare if a patient is able to insert and remove the pessary on her own and thus remove it overnight at once per week.

Suggested Sequence for Fitting Pessaries for Prolapse: before a pessary-fitting session, all women with even slight vaginal atrophy are pretreated for 6 weeks with estrogen cream. Women are instructed to come to the fitting session with a moderately full bladder. For women with stress incontinence, this allows testing of the efficacy of the pessary, and for women with prolapse, this determines whether reduction of the prolapse is accompanied by incontinence. In addition, all women attempt to void with the pessary in place before leaving the office. Women are instructed to mimic vigorous activity in the clinic area (such as brisk walking, jumping jacks, straining), and the patient is then sent home with the best fit. Once home, the best fit in the office fails for approximately one fourth of women, who then return for further fitting.

Our recommendation for follow-up care is - First follow-up visit (1 week; 1 to 3 days for Cube). Examine vagina, adjust type and size as needed. Teach insertion and removal; because women in our practice generally remove the pessary at least once a week, they rarely encounter excessive or malodorous vaginal discharge and thus have little use for creams other than estrogen.

Long-term follow-up - for woman who can insert and remove pessary; return visits: 2 weeks, 3 months later, every 6 to 12 months. Instructions given to patients to remove pessary each night or at least once per week; leave it out overnight and use estrogen cream on pessary as lubricant.

Women who cannot insert or remove pessary - should be seen in 2 weeks, 4 weeks later, 6 weeks later etc. up to 3 months. Determine appropriate pessary removal interval and optimal - remove and have visiting nurse reinsert in morning (or vice versa). Triple sulfa cream or acigel may decrease discharge.

Vaginal Devices and Suggested Sequence for Fitting Pessaries for Prolapse / Incontinence

Surgical Management - the vaginal approach to pelvic reconstruction has the advantage of access to all three segments of prolapse, the anterior and posterior vagina and the apex, as well as the ability to perform procedures for stress urinary incontinence that commonly coexists with prolapse, via the same approach. Perineorrhaphy and posterior colporrhaphy are most easily accomplished with a vaginal approach. Cystocele traditionally is repaired vaginally via anterior colporrhaphy, with failure rates of up to 40%. Three commonly used techniques of anterior colporrhaphy are: standard plication, standard placation reinforced with polyglactin 910 mesh, and ultralateral dissection with plication. Vaginal repair of uterine or vaginal vault prolapse requires resuspension of the vaginal apex to ligamentous or connective tissue supports in the pelvis. The most common structures used to resuspend the prolapsed vaginal apex are uterosacral and sacrospinous ligaments. Many pelvic floor surgeons prefer the uterosacral to the sacrospinous vaginal vault suspension because of better restoration of normal vaginal axis anatomy and decreased recurrent anterior vaginal wall prolapse following vaginal hysterectomy. Stress urinary incontinence commonly coexists with prolapse, and can be repaired vaginally with sling procedures.

Patients rarely have an isolated enterocele; hence, concurrent vaginal vault suspension and rectocele repair often are necessary. The enterocele sac should be mobilized from the vaginal walls and rectum. When the enterocele sac is difficult to distinguish from the rectum, differentiation is aided by a rectal examination with simultaneous dissection of the enterocele from the rectal wall. After the enterocele sac has been dissected from the vagina and rectum, traction is placed on it; the sac is explored digitally to ensure that no small bowel or mental adhesions are present. If encountered, they are dissected to the level of its neck. Under direct visualization, two or three circumferential non-absorbable, purse-string sutures are used to close the enterocele sac. The cardinal-uterosacral ligaments are incorporated as well. Once in-place, the sutures are tied in sequence. Care should be taken to avoid kinking the ureter. Posterior colporrhaphy to repair rectocele and vaginal vault suspension are performed as indicated.

Conclusion:

Unfortunately, no treatment exists that cures all women with stress incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse 100% of the time. Surgery, long considered the gold standard for treating these conditions, loses some effectiveness with time, such that the 80% to 90% cure rate seen 2 to 5 years postoperatively decreases to 50% to 60% 10 years later. Although conservative management cures far fewer women than surgery, the decreased risk and expense combined with the reasonable improvement rates associated with conservative therapy make this approach attractive as a first treatment option for most women.

All health care workers should be sensitized to the wide-spread existence of this condition. Every woman needs to know that the condition is curable. Patient education about the various treatment modalities available and their success rate will help motivate suffering women to reach out for medical help. Higher female literacy and socio-cultural changes that emphasize the needs of women for education, health care and gender equality issues can have a marked effect on incidence of this highly preventable disease. A genuine effort at prevention may lead to this disease becoming relegated to only medical history textbooks.

Published: 9 February 2009

Dedicated to Women's and Children's Well-being and Health Care Worldwide

www.womenshealthsection.com